(I’ve been reading the stories that got both Hugo and Nebula nominations. To see all the posts in the series, check the “Joint SFF Nominations” tag.

Because this one was running long, I decided to split it into two parts. Before reading this you’ll want to check out the first half, which among other things includes the story list.)

Possession

Robert Silverberg’s “Passengers” isn’t as excruciatingly uncomfortable as “A Boy and His Dog” but isn’t great. In the story’s world incorporeal “Passengers” take people’s bodies on joyrides. (These sound more like drivers than passengers, but never mind.) Victims are conscious during the possession but normally remember nothing afterwards. Charles wakes up after a Passenger used his body for sex with a Passenger in the body of a woman named Helen. He remembers his possession and recognizes Helen on the street. She has no memory of Charles. Charles decides he and Helen are meant to be together and chats her up. When he admits they were possessed together she’s repulsed, but immediately gets over it. Just as it looks like Charles will get lucky another Passenger possesses him and makes him walk off with a man.

Some SFF stories are metaphors, but also literal in a way absurdist or surrealist stories aren’t. Neither level needs to work perfectly (and the literal level doesn’t always entirely need to make sense), but it helps if neither goes entirely off the rails. “Passengers” has problems on both levels. Literally, Charles is trying to pick Helen up knowing important information about her while Helen knows nothing whatsoever about him. In other words, he’s a stalker. And when Charles runs into Helen after his possession it’s hard to believe he’s attracted to her and not newly traumatized. And after Helen learns what’s happening she goes from horrified to okay like the author flipped a switch. “Passengers” does not deal honestly with the emotional implications of its premise.

Metaphorically, Charles and Helen had an impulsive one night stand and now Charles wants a relationship. “Passengers” is concerned with free will: “It is the old problem, free will versus determinism, translated into the foulest of forms. Determinism is no longer a philosopher’s abstraction; it is cold alien tendrils sliding between the cranial sutures.” Charles ponders whether he can tell the difference between his own choices and choices a Passenger made for him. “Did we ever have more than that: the illusion of freedom?”

But as a metaphor for the forces that actually constrain people’s choices—economic, social, psychological—the Passengers don’t work. Real determinism is “I have to keep the job that expects me to work sixty hour weeks because I can’t afford to lose my health insurance,” or “I can’t take on another project because with my Attention Deficit Disorder I can only handle so much.” Passengers just make people act randomly: “I slept with that woman because I couldn’t help myself.” That’s not a constraint, that’s a whim. “Passengers” feels less like a serious meditation on free will than an evasion of responsibility. Literally it’s a tragedy; metaphorically, it’s a fantasy of blamelessness.

“Dramatic Mission” is the third and last time Anne McCaffrey turns up in this series. I’d like to insightfully sum up her stories but, honestly, I’m just bored. Like the two Pern novellas, “Dramatic Mission” is awkwardly written and glacially paced. The characters are so shallow I had trouble recalling who everyone was, or even how many characters there were. And all three stories bury weird unexamined assumptions in their worldbuilding. Here, Helva is a human born with significant (I assume potentially fatal) physical disabilities who was given a spaceship for a body… and told she had to work off the cost. She literally needs to “buy herself back from Central Worlds.” A few paragraphs later the story says “According to Central Worlds’ charter, no sentient entity could be placed in a condition suggesting peonage,” but what did you just get done telling us, Anne?

Helva’s latest job is to ferry a troupe of actors to an alien planet to introduce them to Shakespeare.[1] Following an interminable exploration of the cast’s ironically undramatic interpersonal problems, they upload themselves into alien bodies to perform the play.

As with the Pern novellas I assume “Dramatic Mission” was doing something sixties SFF fans weren’t getting anywhere else. It’s preoccupied with bodies, and exchanging bodies. Helva’s exchanged hers for a spaceship. The actors project their minds into specially-created alien bodies, and three decide to keep their new forms. SFF has traditionally been a geek interest—far more so fifty years ago than it is now—and sometimes geeks have complicated relationships with their bodies. Modifying and exchanging bodies are common themes in SFF, and common fantasies. (Heck, part of the reason Doctor Who always appealed to me is probably the main character’s ability to be different people.) Maybe a certain part of McCaffrey’s audience would have loved to be a spaceship, just as others wanted to ride a dragon.

The Disenchantment of the World

“Not Long Before the End” is secondary world fantasy. “Secondary world” is a term coined by J. R. R. Tolkien for a fantastic invented world, like Middle Earth or the setting for a game of Dungeons & Dragons. This series has covered Twilight Zone-style contemporary fantasy, and science fiction worlds with a fantasy aesthetic, but this is our first story that’s what most fans have in mind when they say “fantasy.”

Tolkien isn’t yet a big influence. This is sword and sorcery, influenced by Robert E. Howard’s Conan. There’s not much to it beyond the reveal of its central gag, but there are a couple of interesting things about that gag. Magic is a non-renewable resource: cast too many spells in the same place and it’s gone. This is, first, the kind of nerdy plot-hole patching story I mentioned way up in the section on “Time Considered as a Helix of Semi-Precious Stones.” The conceit of the Conan stories was that they were set in real history at some unspecified time. Niven is explaining why magic worked then but not now.

Second, like “A Boy and His Dog” this is a world that’s decaying. Niven’s world is being literally disenchanted—losing its magic literally and figuratively. It’s losing the specific quality that defines its genre.

That’s also true of “Deeper Than the Darkness,” a space-opera story that ends with humanity retreating from space: “The men who climbed to the stars now cower in caves, driven by the horrors they inherited from the first amphibians.” It’s one of the most blatant Cold War stories we’ve covered. “Deeper Than the Darkness” pits individualism against collectivism, but in a way that’s weirder, more oblique, and less straightforwardly conservative than you’d think. (Gregory Benford would later expand the story into a novel, then write a revised version called The Stars in Shroud.)

Earth has gone in for collectivism, not because the communists won the Cold War but because capitalism defeated itself. Almost all the Americans died in the “Riot War.” (Again, the late 1960s saw a lot of protests end in violence.) Our protagonist, starship captain Sanjen, is one of the survivors’ last descendants. Sanjen keeps his crew unified by leading them in Sabal, a complicated game with elements of the Prisoners’ Dilemma, the game theory scenario in which two people have to cooperate without knowing the other’s decision. Humanity has blundered into conflict with the Quarm, a species so individualist they can’t even stand themselves. As the story opens Sanjen is rushing to a colony planet to rescue the survivors of a Quarm attack.

What he discovers is weirder than anyone expected. The colonists have filled their complex with dirt and are hiding, and dying, in cramped tunnels. This whole sequence is genuinely claustrophobic and unsettling. Worse, after Sanjen brings the survivors on board his crew become afraid to leave their cabins. The Quarm weapon reawakens ancient prey instincts, making humans fear light and open space. And humans are so interdependent and group-oriented their psychology is infectious, like a mental computer virus. Sanjen can’t get anyone to understand what’s happening until it’s too late: “the ideals my ancestors held were called a temporary abnormality, a passing alternative to the communal, the group-centered culture… But we had met something new out here, and I knew they wouldn’t understand it. Perhaps the Americans would have, or the Europeans.”

But this isn’t straightforward anti-communist propaganda. The Quarm virus also turns people away from community, making them self-absorbed and withdrawn. They stop communicating. The first sign of trouble is when the Sabal games fall apart. Sanjen”˜s warnings fail after he’s undercut by his first officer; a new individualism is manifesting as ambition.

In a way, this is possession again. People’s entire psychologies are being rewritten from outside. This time possession stands in for paranoia over cultural change. The Quarm win not by fighting but by injecting alien values into Sanjen’s culture, mutating it beyond recognition. This is what conservatives saw as the left embraced anticapitalism, but it’s also how the left felt watching Nixon (and, much later, Trump) take office. It’s a complex metaphor. That’s the best kind.

In “Ship of Shadows” Earth is, again, dying—although we don’t learn that for a while. Spar, a drug addict, believes the spaceship where he lives is all the world there is. In a way that’s true, because this story is about what’s going on inside Spar and his world is a metaphor for his self. A spar, after all, is part of a ship.

The Windrush is a zero-gravity plastic maze of shrouds and towlines and translucent sails. It’s almost abstract, like a set for a minimalist play. The abstraction is heightened by Spar’s nearsightedness. Until he gets glasses the environment is described in blobs and blurs. Getting dentures and a good pair of glasses is Spar’s main motivation; this is a mood story, not a plot story.

“Shroud” also suggests burial shrouds. The Windrush is unexpectedly gothic. As the story opens Spar picks up a familiar, a talking black cat. The crew is amnesiac; hardly anyone remembers there’s an outside world. (At one point Spar sees a picture of a woman and wonders what’s pulling her hair and clothes towards her feet. He’s forgotten gravity.) Everyone’s afraid of witches and vampires. In the latter case, they’re right to worry. The local crime boss, Crown, is pulling a Peter Thiel. He and his vampire brides survive on other people’s blood. (Charmingly, they stick drinking straws into their victims’ necks.)

Once Spar walks in on Crown’s drinking session the denouement is perfunctory. Crown is defeated, and in a few rushed paragraphs everyone tells Spar who he really is and that he needs to take charge of Windrush: “Doc said, ”˜So, Spar, you’re the only one who remembers without cynicism. You’ll have to take over. It’s all yours, Spar.’” Exactly how he’s meant to take over is unclear, but also beside the point. Gaining control of the Windrush is a symbol of how Spar has kicked his addiction, regained his self-respect and self-control. (Fritz Leiber himself struggled with alcoholism at points in his life.) This is a psychodrama, and if the literal level is a little handwavy on the details it doesn’t derail the story as in “Passengers.”

Spar learns Windrush is a lifeboat.[2] Earth is dying. Which is interesting, because it’s gratuitous—the story would work if Spar were on the Windrush for any reason at all. The end of the world is just assumed.

Things Falling Apart

So, to recap, we’ve seen:

- A generic post-nuclear wasteland in “A Boy and His Dog.”

- The fall of America and humanity’s retreat into agoraphobia and solipsism in “Deeper Than the Darkness.”

- The literal disenchantment of the world in “Not Long Before the End.”

- The loss of free will to unstoppable, incorporeal aliens in “Passengers.”

- The destruction of Earth and near-universal amnesia in “Ship of Shadows.”

And in “To Jorslem” Earth, in decline after a worldwide environmental disaster, finally falls to alien conquest. These worlds aren’t just falling apart, they’re unfixable. The stories that resonated with SFF fans at the end of the sixties did not offer easy hope for the future.

Fifty years on, pop culture remembers a cartoon version of the Sixties. Bright colors, psychedelia, Sergeant Pepper and Yellow Submarine, peace signs, Mr. Spock jamming with nonthreatening hippies. But the United States in the late sixties would have been an alarming time and place to live in—a cycle of war casualties, violent protests, assassinations, and Richard Nixon repeatedly refusing to go away. As I say this, bear in mind I wasn’t born yet in 1970. I’m looking at it through five decades of hindsight. But I wonder whether these stories resonated because their readers feared their world was broken beyond repair.

(We’re in a fraught time now, and it’s interesting to compare this year’s Hugo and Nebula awards. The short story ballots are dominated by gentle, consolatory stories, often written in a style I associate with children’s stories. Even one of the more pessimistic stories, a zombie apocalypse, is more about showing off the protagonist’s badassery than about horror.)

There’s one story left, and it’s one of the falling-apart stories. But it also offers some optimism.

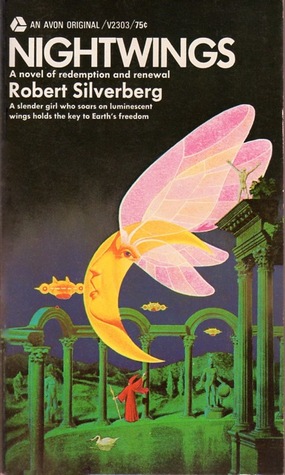

“To Jorslem” is a sequel to last year’s “Nightwings.” In fact, it’s the second sequel. Having written the first novella Robert Silverberg wrote two more and published them as a novel, also titled Nightwings.[3] In “To Jorslem” we rejoin the Watcher, now calling himself Tomis, as he travels to Jerusalem (Jorslem) as a pilgrim on an occupied Earth.

We’ve skipped the middle novella, where Silverberg put the exposition; Tomis spends most of it researching Earth’s history. In the Second Cycle humanity kidnapped less advanced species and put them in zoos. Meanwhile they started a massive geoengineering project to control the weather. This was a bad idea; it ruined the climate and destroyed North and South America. (Again we have a story where the United States, specifically, is gone.) One of the species whose people were abducted bailed humanity out on the condition that Earth belonged to them whenever they were ready to collect. The invaders’ claim to Earth is legitimate.

I said last time Nightwings feels like a Jack Vance story where not everyone is an asshole. It’s full of weird, impressionistic details. It’s good at creating the impression that these characters don’t share a frame of reference with us while keeping them relatable and human. There’s an incongruous mix of magical technologies and atavistic social structures and a weight of history and science learned and forgotten again.

Jorslem is still a holy city, but these days people believe in “The Will.” “The Will” is a generic force of the type that, if you’re in the mood to be unkind, could be recast as “The Plot.” What it feels like is the force of history. As one character puts it, “The Will does not shape every event great or small; it provides the raw material of events, and allows us to follow such patterns as we desire.” The Will is the choices of others in the past that limit the choices of people in the present, the social context that narrows people’s options—what Silverberg’s Passengers were meant to be, but aren’t.

Ancient technology in Jorslem can restore a pilgrim’s youth, if they’re worthy. Tomis passes the test. His renewal is a full-on psychedelic trip with hallucinated guest appearances from everyone he’s ever met. Speaking of which, in the real world he reconnects with the Flier Alvuela, who tells him she has a new guild he can join, the Redeemers. This is weird; there’s no logical reason for her to be in Jorslem. After declaring her love for Gormon in “Nightwings,” which ended with her symbolically taking off into the sky with him, we’re told they immediately broke up. It’s like once Silverberg decided to expand the original novella he thought Alvuela needed to end up with Tomis for purely structural reasons. Her characterization feels disjointed. But part of the point of the original story was that Tomis didn’t totally understand her in the first place, so maybe that’s not a problem?

The arc of the novel moves towards understanding: from Tomis’ early obliviousness in “Nightwings” to the middle section’s deep dive into human history to the total understanding practiced by the Redeemers. The Redeemers have found a way to enter a telepathic gestalt in which they can feel others’ thoughts and sensations; at the end of “To Jorslem” Tomis mentally flies with Alvuela as Gormon did physically at the end of “Nightwings.” This is another kind of possession, but again it represents a different idea. This is benign, consensual possession—no one in the link loses their identity or individuality, they’re in direct mind-to-mind communication. Basically, radical empathy. The Redeemers are going to “solve” the invasion by accepting that the invaders are here because of the choices of humans who came before, and eventually accepting them into the human gestalt.

In most of these stories, Earth in general and America in particular is hopelessly dead or dying. “To Jorslem” is the one story to suggest building back up from the rubble. Our options may be limited by choices made by people who came before us, but we have enough free will to choose the best of the ones remaining to us.

I’m going to be continuing this series and I’ve started working on 1971, but there might be one or more unrelated posts in between, as I’m currently weary of overwhelmingly male-dominated shortlists. The next installment will probably come within the next month.

-

As in Star Trek, the people of the Central Worlds just happen to enjoy drama in the public domain as of the mid–20th century. Funny how that works out! ↩

-

It’s not clear whether this is a reference, but a ship called the Empire Windrush was one of the first ships to bring Carribean immigrants to the United Kingdom; people who came to the U.K. from those countries after World War II are often called the “Windrush Generation.” ↩

-

In the novel this story is called “The Road to Jorslem.” The editor changed it because it sounded like a Bob Hope movie. ↩