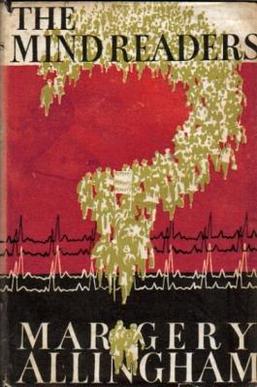

A well structured novel isn’t the same thing as a good novel. The Mind Readers, Margery Allingham’s last Albert Campion mystery[1] is a case in point.

By the standards of the novel-writing advice industry, The Mind Readers is a lean-to made of tinkertoys and string. The plot is disjointed. Characters drop in and out. The scene that feels like the dramatic climax comes before the actual climax, in which Campion passively watches a lengthy TV broadcast that functions as extended infodump and deus ex machina in one. But The Mind Readers is weirdly compelling. A less idiosyncratic novel wouldn’t have the same effect.

Allingham was one of the best golden age mystery writers and also one of the most underrated. She’s a better writer than Agatha Christie (though no one beats Christie at constructing puzzle plots) and I’d rate her best work alongside Sayers. She was always trying something new. The Campion books ranged from pulpy adventure to straight mysteries to character studies of criminals. She was still experimenting in her last book: The Mind Readers is science fiction. And though the iggy-tubes aren’t remotely plausible this is actual SF, not a detective story with a sci-fi MacGuffin: the exact properties of the SF element are tied to the novel’s themes.

The plot kicks off when Campion’s wife Amanda’s nephews[2], Edward and Sam, come home from school for a visit. They’ve brought a gadget they call an “iggy-tube” that, placed against the jugular, makes them telepathic. It’s not clear where they got the thing. There’s some suspicion it came from the island-based government research facility where Sam’s father works. (As anybody who’s read The Men Who Stare at Goats knows, in the 1960s governments were genuinely investing in ESP.) Well, where else could it have come from? It’s a breakthrough.

We learn why a scientist might have handed the iggy-tubes over to schoolchildren when Campion’s colleague Sergeant Luke tries one out. It’s traumatizing, overwhelming mental chaos, a tangled forest of thoughts and feelings, not all happy: “I thought they were all mine and it scared me stiff.” The kids don’t have the same problem. They don’t have the life experience to recognize the more difficult parts of the subconscious, or associate fraught emotions with painful memories. They haven’t yet learned to draw back from the forest; they’re not too panicked to weave their way through to the thoughts they want to receive. “The less you know the less you are afraid of the unknown,” as one character sums up.

There’s one problem: Sam has kept his iggy-tube connected too long. Without it, he turns vague and uncommunicative, and it’s a couple of days before he’s back to normal. Sam has temporarily forgotten how to function as an individual instead of a relay point in a grammar-school gestalt. Amanda’s nephews are turning alien.

Meanwhile, the adults are anxious. What does it mean for privacy when anyone can read your mind? (Only kids can use iggy-tubes now, but it’s early days; whoever built them will come up with an improved model.) More to the point, what does it mean for the intelligence community? Won’t someone think of the spies? Edward and Sam are nearly kidnapped by a politely nameless foreign power. Meanwhile a peer named Lord Ludor puts the island lab on lockdown. Ludor is the kind of man who’ll torpedo your career if he thinks you haven’t shown him proper deference. Telepathy could help Ludor control people or put them beyond his control entirely, depending on whether he’s the mind reader or the mind getting read.

Campion is on the island when it’s closed and is stuck there for a large chunk of the novel. Looking for a way out, Campion runs across an old acquaintance, an ex-crook and surveillance expert turned “lonely old man of the sea” surrounded by young technicians. He seems desperate for Campion’s company, which reminds him of when he felt relevant. But Campion feels extraneous himself. Not for the first time in the series–he makes not much more than a cameo appearance in Hide My Eyes. But this time the narrative focus stays on Campion while the real action is elsewhere–Edward has now disappeared entirely. Both Campion and the readers are sidelined together.

Here the murderer waylays Campion on the road. A lot of modern genre novels feel like attempts to recreate Hollywood summer blockbuster thrillers on paper, but a suspense scene can be a quiet conversation instead of a breathless set piece, and in a book that often works better. The confrontation with the culprit is the best written part of The Mind Readers, and it functions as exposition and suspense at the same time. It’s exposition as chess match: Before the culprit puts Campion out of the way he needs to know what Campion figured out, and when, and who else knows. Campion needs to put his death off as long as possible while learning everything the culprit knows about the plots surrounding the gadgets. Every line of dialogue is a calculated maneuver. Campion never gets the upper hand; when the confrontation turns physical, his enemy is younger and stronger. He’s rescued because Sam telepathically overheard his panic.

Unlike Hercule Poirot or Nero Wolfe, Campion aged in real time; according to Allingham he was “the same age as the century.” The Mind Readers was published in 1965, which puts him at retirement age. Campion’s ankle hurts and he’s exhausted. He’s old, and for the first time he feels it.

It’s a great scene; whatever flaws The Mind Readers might have, Allingham is at the top of her game. Which raises the possibility that the flaws aren’t really flaws. Keep that in mind during the last two chapters which, judged by the current consensus on how stories are supposed to work, are very weird.

The book ends with heroes and villains alike gathering to watch a television program on Amanda’s advice (delivered through the surveillance Ludor has put on her house). It’s a talk show. The guest is Edward. The host proceeds to deliver two chapters of exposition about everything that’s gone on in the background while Campion was on the island. Most of these two chapters are a transcript of the broadcast, which the reader watches along with Campion.

In short, no one gave Edward the iggy-tubes–he developed them himself. (It’s a long story involving some weird transistors found in a batch of ordinary radios.) Before the book even started he was testing the tubes with his classmates and writing up his findings for a junior science magazine (the TV host reads his letter out in full). After the kidnapping attempt Edward arranged his own disappearance, again coordinating with his classmates as well as Amanda. Then he went to a newspaper and demonstrated an iggy-tube to the editor, who set him up with the TV host.

What’s notable is not just that Allingham has ended her novel with a two chapter infodump. It’s that the broadcast takes the patient, reassuring tone of children’s television, like an episode of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood. (“Above all, do not be afraid. Your secrets are safe for a very long time.”) But it’s not the kids who need reassuring; they handle ESP just fine. The host is reassuring the grown-ups, who have discovered they’re irrelevant.

Two nations’ intelligence services spent the entire novel on a wild goose chase. The murder of the scientist achieved nothing. Campion, Sergeant Luke, and Lord Ludor were looking in every direction but the right one. Edward was in charge all along, and everyone else can only watch while he announces the fact on live television. Ludor is defeated by learning the situation is just plain out of his hands. His one last stab at relevance is to try to get the kids on side, offering them a job as soon as they’re out of school, but Sam shoots him down: “‘It’s very kind of you,’ he said seriously. ‘But do you think you ought to promise? There’s going to be a lot of change in the next ten years. You may not have anything for me to do.’”

And, yes, I know this sounds massively unsatisfying. The threads we were following never mattered and now they’ve been suddenly, neatly severed by a deus ex machina. It’s like everything we cared about for the last 150 pages was a waste of time. But it’s the perfect ending for this book, because it puts the readers in the same position as Campion. The rug’s been pulled out from under us by a clever kid who never meant us any harm but inadvertently left us feeling irrelevant and foolish.

The point of a novel isn’t to tell a clockwork-perfect story, with a well-crafted structure and all the beats in the right place. The point is to get the reader to experience certain feelings and think about certain ideas, which as far as I’m concerned Allingham manages here. Sometimes a weird and ramshackle novel has tools that aren’t in a well-crafted but conventional novel’s toolbox. Weird tools, with neon paint jobs, unexplained dangly bits, and racing stripes.

What Allingham is feeling here, the theme she’s grappling with, is how time and change seem to accelerate with age. When Allingham published The Crime at Black Dudley in 1929, television didn’t exist. Neither did the atomic bomb. Everything was getting stranger. If she was still finding new things to do with Campion it’s partly because so many old stories–the boys’ own adventures of the early novels, the polite high-society crimes that followed–didn’t make sense in this new world. In The Mind Readers she ushers Campion into a future that may not need detectives at all, much less detective-story novelists. Allingham’s husband completed one more book and wrote a couple of sequels of his own, but this feels like Campion’s last adventure–no big final act, just life overtaking him and leaving him behind. Maybe it’s time for the kids to start running things.

And maybe that’s okay? Again, that two-chapter infodump feels reassuring, like a trusted parental figure talking her fellow parental figures down from a panic. The sixties were a decade when a lot of older creators started getting cranky about The Kids These Days. Margery Allingham has seen the future. It’s bewildering, and she’s not sure she has any place in it. But she also seems to think the kids might be all right.

Allingham doesn’t have a simple message to impart. She’s working through ideas and feelings she isn’t sure about. I love novels that explore ideas without being sure where they’re going, and try to do too much, and seem to be doing some of it accidentally. They’re often more interesting and powerful than novels that know exactly what they want to say, and say exactly that. The Mind Readers is not a great book, and in some ways not even a good one, but it sticks with you. It’s good for stories to be a little messy.