1.

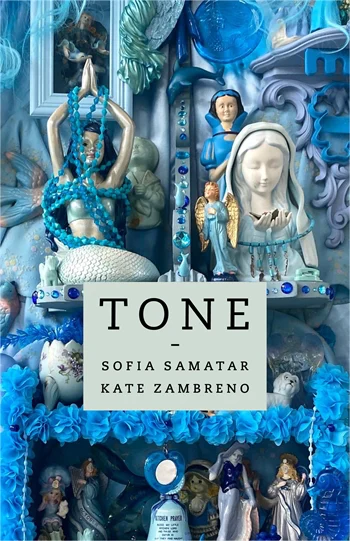

What I mean is, I’m writing on Sofia Samatar and Kate Zambreno’s book Tone, not their, y’know, tone. Although that’s interesting, too. This is imaginative criticism, not dryly analytical but poetic. Books about art can also be art.

Tone, as a literary concept, isn’t as easily defined as plot or character. “Tone” seems to mean less the more you repeat it. (Tone. Tone? Tone tone tone.) Online literary discourse (and it is mostly discourse, in its incarnation as the term for sniping and squabbling on various Twitter methadone sites, rather than discussion or conversation) hinges on plot, character, and visible surface politics, and not much else. Tone mostly comes up in the context of accusations that someone is trying to police it. You start to feel like any consideration of it is cop-brained.

But it does mean something, albeit something elusively complex; Samatar and Zambreno are approaching a definition, not declaring one finalized and laminated for safekeeping. Singular authority is what this book is running from; it’s written in first person plural for a reason.

2.

It’s not voice, for one thing. A book with a consistent tone can contain many voices and one voice can speak in different tones. Readers often have very different feelings about the first three Earthsea books and Tehanu. (I’m lukewarm on the former and loved the latter.) They’re all in Ursula K. Le Guin’s voice but she’s writing in different tones.

Some of the metaphors Samatar and Zambreno use to approach tone:

-

Windows. (Lighted windows, stained glass windows, computer windows.) A window frames what you see through it, maybe colors it. You can be inside looking out or outside looking in. Is this the difference between the writer and the reader? Which is which?

-

Synesthesia. Tone can be a color—some books are grey, some blue. Tone can be an odor or a background noise. Sense-impressions create atmospheres; atmospheres remind us of sense-impressions.

-

Speaking of atmospheres: Ecology. Tone is established through relationships—how the materials of a text relate to each other in a complex web, like the elements of an ecosystem.

Samatar and Zambreno illustrate their arguments with close readings of several novels, and their reading of W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn lays out (even for someone like me who has not yet read it) how the ecological metaphor works. Samatar and Zambreno argue The Rings of Saturn has a distant tone, an atmosphere of parts:

- The Rings of Saturn is structured by a long walk through Sussex—a distance travelled horizontally—after “a long stint of work.”

- The book repeatedly watches things from heights—from a cliff, a plane, the top of a well.

- There’s a model of the Temple of Jerusalem, which not only seems distant—we look down on models like we’re looking from a great height—but models something distant in time. The novel ponders the history of the territory the narrator walks (and “the traces of destruction, reaching far back into the past, that were evident even in that remote place”), and also thinks for a while about the 17th century writer Thomas Browne.

- Sebald’s prose is itself old-fashioned, temporally distanced, originally written in an archaically-tinged German.

Writers arrange images, incidents, and language to resonate against (or with) each other. And then this feedback loop happens: the resonance becomes an organizing principle in itself; readers interpret images, incidents, and language through the tone.

3.

Tone is a general exploration of tone, and also offers readings of several specific books, and at a certain point you realize you’re also reading cultural criticism. Samatar and Zambreno are writing about the tone of the world—the affective atmospheres we breathe without noticing.

The books Tone analyzes, in relation to each other, set a tone—Nella Larsen’s Quicksand, about a Black woman academic; Heike Geissler’s Seasonal Associate, about a writer working a temp job at an Amazon warehouse; Hiroko Oyamada’s The Factory, about people working absurd, meaningless jobs; Sebald’s meditations, which take in historical disasters. Samatar and Zambreno investigate tones specific to their own experiences as women in 21st century academia (the atmosphere breathed by a visiting scholar, for instance) and more broadly the tone of the world everyone shares, where capitalism is a sickening and collapsing end in itself instead of a means.

Tone is about the relations between elements in a text, but it’s also about seeing the relations between people in a culture that atomizes us and nudges us into an individualist mindset: we’re the hero, others supporting extras. In the end, Tone concludes, the book has been as much about “making a space where certain things can be said” as about tone itself.

Good criticism, like any other kind of good writing, has got to do more than one thing at a time.

4.

These points where Samatar and Zambreno talk about tone in ecological terms struck me hardest. Another word for an ecosystem is the environment. “Environment” can also mean a social or cultural or architectural environment. In any case it’s an arrangement of materials that relate to each other in particular ways and create particular effects (or affects), and we are among those materials in both senses of the word.

In the Peanuts strip that ran August 11, 1970, Linus is just back from a trip. Everywhere he went he saw the same malls and motels and restaurants they had back home. “Every town looks like every other town… It doesn’t matter where you go… you never left!”

A lot of SFF books—popular fiction in general, really, but SFF is the genre where I keep most up to date—feel like featureless lumps of gray teflon. My attention slides off them. I’ve always found the reasons hard to pin down—nebulous and most likely myriad. But one piece of the puzzle that is my alienation from pop culture is likely a loss of cultural biodiversity. 21st century SFF favors reboots and retellings. It’s marketed as bullet lists of safely familiar “tropes” legoed together into microtargeted subgenres. Every book needs its comp titles; the most marketable use mostly the same materials in mostly the same configurations.

Tone is part of this. High-profile SFF stays within a limited range of marketable tones—straightforwardly invisible, snarky, heartwarming, spunky (this last usually written in first person present tense). SFF paints deep space, fairyland, and contemporary New York in the same tones; they color the speech of medieval Europe, the Paleolithic tundra, and posthuman Pluto. Tonally, these stories are interchangeable geography-of-nowhere theme park suburbs. A literature where, no matter where you are in space or time, you can always get McDonalds.

(It’s easy to see why media execs are comfortable with AI art: AI is inherently remixed, no potentially off-putting tone of its own. A portfolio of proven successes blended into a palatable Soylent shake.)

Samatar and Zambreno quote a speaker at a conference who says Kafka’s style is unlike any other kind of German, like a “meteor” fallen to earth. What with the books’s focus on relationships I don’t feel like it makes sense to talk about this as individuality of tone. Maybe specificity is the right word. Kafka compels because the tone of his work, like the language, is determinedly specific.

Samatar and Zambreno write that the most compelling reason to return to a book is “to breathe that air again.” But first it needs air of its own.