Popular history is often written like a novel, shaped into the kind of story for which an author might sell movie rights. It’s possible to write good history like this, but it has to be a particular kind of history, focused on people who resemble protagonists and events that can be arranged into plot arcs. Zephyr Teachout’s Corruption in America is another kind of history underrepresented on the bestseller lists–the story of an idea and a legal concept. Teachout describes legal cases and court decisions in terms non-lawyers can understand, and the deeper beliefs about corruption that drove them. The book doesn’t need dramatization, or formulaic biographical sketches of the participants, or any of the usual human interest tricks of bestseller history. The subject is interesting in itself: an argument in response to the Citizens United case about how the United States has understood corruption and how we ought to understand it.[1] (It’s a pretty wide-ranging book. This post shouldn’t be taken as a comprehensive review; it’s more me talking to myself about some bits I found interesting.)

Corruption in America defines corruption as the use of public power to further private interests at the expense of the public good. What the public good is, and when we can say for certain private interests are being pursued at its expense, are not always clear. Take the Credit Mobilier scandal. The Credit Mobilier company existed to skim excess profits off railroads; what’s relevant here is the cheap stock sold by congressman Oakes Ames to colleagues who voted on railroad funding. When the details came out, part of Ames’s defense was that he didn’t need to bribe anybody: everything was going great, Congress was very pro-railroad, so where was the motive?

He had a point, sort of: corruption can be nebulous. Did Senator Jones vote for the artichoke bill because of the campaign contribution from Big Artichoke, or did the artichoke PAC donate to his campaign because it knew he really loved artichokes? That’s why we have what Teachout calls structural or prophylactic regulations. These set bright lines officials cannot cross, like the constitution’s now-famous emoluments clause[2]: “No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States: And no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.” No need to establish motivation, or prove a quid pro quo: ban presents of any kind whatever and you remove the temptation to turn a gift into a bribe. Instead of watching for scandals and proving motives in court, change the incentives. It’s the difference between treating a disease and getting vaccinated to keep from catching it in the first place.

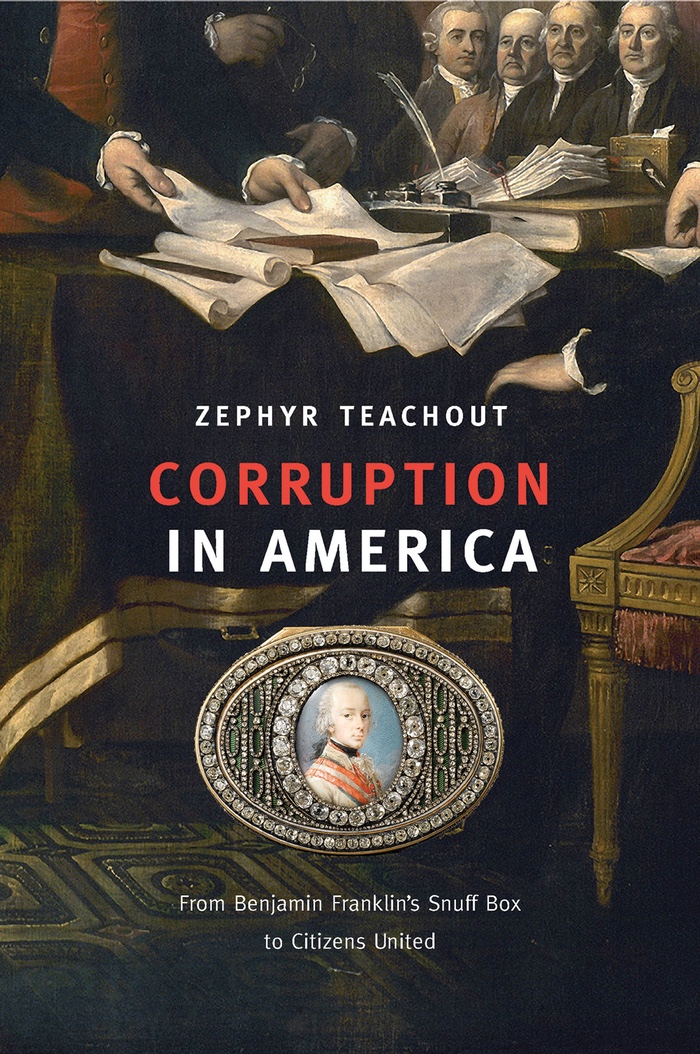

The emoluments clause exists because in 18th century Europe it was de rigueur to shower foreign ambassadors with lavish gifts. The iconic example for Corruption in America is a diamond-encrusted snuff box the king of France gave Benjamin Franklin: that’s it on the cover. Franklin’s snuff-storage problems notwithstanding, for Americans this was exactly the kind of archaic old-world decadence they wanted to do away with. It wasn’t that Americans didn’t trust Franklin, or any ambassador in particular: even in the absence of any specific scandal, emoluments were a moral problem. Gifts create a sense of obligation between givers and recipients. Who could say whether that sense of obligation was stronger than an ambassador’s sense of obligation to the public? Could even the ambassador know for sure? “Offices,” whether patronage positions or expectations of post-government jobs, might be even worse: they created dependencies, encouraging officials to put their employers before their public.

The United States had a representative government. Officials who furthered their personal interests, or the interests of their friends, at the expense of the public interest deprived citizens of representation. Creating a situation that tempted officials to put their private loyalties above their loyalty to the public–letting them accept gifts, or promises of sinecures, for instance–would rot the whole system.

Ideas about corruption have changed since then. Lobbying is a useful example. Lobbying got its start in the 19th century, when lobbyists literally hung around capitol lobbies. This was not a respectable career choice. There were two problems with lobbying (or maybe two facts adding up to one problem, since neither was automatically a problem in itself). First, lobbyists pedaled influence privately, out of the public eye, not just in a courtroom, or before a committee, or anywhere the arguments would be part of the public record. Second, lobbyists didn’t advocate for their own beliefs: their influence was for hire, even to causes they might not personally believe in. Lobbyists sold their personal civic engagement. For many people that was as illegitimate as selling their vote. As a result, courts often refused to honor lobbying contracts: if you agreed to lobby for someone and they stiffed you for the bill, you were out of luck.

Today, lobbying is a major industry. What changed? Well, first, there’s the artichoke problem again: Sure, Senator Jones hangs out with artichoke lobbyists… but what if some of his constituents are artichoke farmers? Representatives are supposed to listen and respond to their constituents. It’s hard to figure out where responsiveness ends and “undue influence” begins. Second, lobbying evolved. As often happens with businesses initially considered weird and dodgy–acting, police work, internet advertising–as people got used to having lobbyists around they went from shady hustlers to professionals. Meanwhile, courts stopped ruling against lobbying contracts. Judges were increasingly reluctant to pass judgement on the content of contracts: where contract law was concerned, courts were laissez faire neutral arbitrators, not moral authorities.

That last change is key: Corruption in America argues that changes in underlying legal philosophy are a major influence on how the United States deals with corruption. Legal philosophy drives court decisions, which decide which laws are valid and how we interpret them. One example of how much the American idea of corruption has changed is the 1999 Sun Diamond decision. Sun Diamond, a trade association, had been fined for giving thousands of dollars in gifts to Bill Clinton’s secretary of agriculture. On appeal, the Supreme Court ruled the gifts weren’t enough to justify a fine: the government had to prove a quid pro quo–unambiguously connect the gifts to a definite “official act.” Otherwise, according to the decision, a high school principal might be prosecuted for giving the Secretary of Education a school baseball cap. What’s striking is that, compared to Americans 100–200 years ago, the court’s priorities have completely flipped. Americans used to be so worried about corruption they wrote structural rules to prevent officials from accepting gifts. The Supreme Court in 1999 was so worried about criminalizing innocent token gifts they ruled against a structural rule to prevent corruption.

Which brings us to Citizens United. This was the ruling that, as long as they weren’t making literal campaign contributions, corporations and unions could spend as much as they damn well wanted to influence an election. (Which is also a campaign contribution of a sort. An indirect one, yeah, but you have to assume politicians keep track of who helps them out.)

Teachout really doesn’t like Anthony Kennedy’s opinion. In her telling it’s not just technically, procedurally bad, but also bad in its underlying assumptions. She has several points to make, but for the purposes of this blog post I’ll look at one.

The opinion rejects the argument that allowing unlimited spending distorts the political process in favor of corporate interests; thus, the rich and the poor alike are granted the right to spend millions of dollars on political advertising. Partly this is because of the court’s habit of treating corporations as interchangeable with individuals. One of the other justifications is more interesting. Quoting his own dissent from McConnell v. FEC, an earlier decision that went in a different direction, Kennedy says “Favoritism and influence are not… avoidable in representative politics. It is in the nature of an elected representative to favor certain policies, and, by necessary corollary, to favor the voters and contributors who support those policies." If favoritism is unavoidable, goes this logic, maybe counteracting it shouldn’t take priority over a corporation’s right to advertise.

This is a practical argument… but it’s a particular kind of practicality that feels familiar. Teachout detects a distaste for democracy in this decision–she thinks it valorizes corporations as information providers while casting citizens in the role of consumers–but I’m reminded more of what Jay Rosen calls the “Cult of Savvy”. Rosen coined the term to describe an attitude he saw among political journalists: as he puts it, “Savviness is that quality of being shrewd, practical, hyper-informed, perceptive, ironic, ‘with it,’ and unsentimental in all things political.” The crucial element of savvy is realism, or something that presents itself as realism. It’s more of a performative rejection of idealism. For the savvy politics is a game, a series of strategic maneuvers. Savvy people are usually ethical in their personal lives, but when it comes to politics calling something strategically or perhaps economically wrong is as close as they come to taking a moral stand. Access to the political system is inherently unequal; representatives naturally favor certain voters and contributors; refusing to accept this is naïve. Regulations written out of idealism instead of hard-headed pragmatism will only lead to unintended consequences.

So Teachout is unsavvy when she argues for a return to older concepts of civic virtue. She frames this as a moral issue, a question of equal access: every citizen has a right to representation, to be heard, to have access to the political process. She argues for structural rules that, if they don’t perfectly guarantee equal consideration and access, at least discourage dependent relationships between public officials and concentrated wealth. The underlying assumptions of Corruption in America’s final argument are that our institutions should be structured not just around the concerns of realpolitik but around our values[3]. And “values” here mean not just what we want these institutions to do (discourage the use of public power for private interests) but the reasons we’re doing it (ideally, everyone should have equal access to the political system regardless of their wealth or power). Ideals are often not actually achievable in the less-than-ideal real world. But it’s not impractical to aim towards an ideal, and count it among the competing interests we weigh against each other when we decide how our institutions will work.

Basically, the argument is that where government is concerned equal access should be a value we treat as important. I have to agree we could stand to work on this: if we’ve learned anything from the town hall meetings of early 2017, it’s that representatives are really unused to listening to constituents.

-

The argument is the weak point of popular narrative history: the less interesting examples tell a story and stop there, without taking a point of view on it. Some things happened, how about that? This doesn’t necessarily make these books read more like novels: any remotely interesting novel is making an argument of some kind, and watching a writer develop an argument can be as interesting as following a plot. There’s even suspense: What’s she building to? Will it be convincing? ↩

-

Whenever I hear the word “emoluments” some small part of me expects muppets to pop up and sing “doo doo de doo doo.” ↩

-

Not that the savvy people don’t have a point when they say idealistic rules and programs aren’t going to solve everything, or that they can go wrong. But “can” does not equal “must.” This isn’t an argument for not having rules at all, but for carefully considering their potential consequences. ↩