Alix Harrow’s fantasy novel The Ten Thousand Doors of January is a very good book, and I enjoyed it. I’m a little conflicted about my enjoyment. The Ten Thousand Doors of January got me thinking about two kinds of subtext running beneath some types of speculative fiction to which it bears a distant family resemblance.

These themes aren’t related–at most, they sometimes intersect–so this essay will ramble, and I’m not sure how coherent it will ultimately be. Just bear in mind I’m not trying to tie everything together; I’m describing a Venn diagram where the circles ever-so-slightly overlap.

Subtext #1: You Flatter Us

There’s a subgenre of science fiction and fantasy written to flatter people who like science fiction and fantasy. Its heroes are smart, imaginative, and interested in strange ideas. In stories set in anything resembling the real world, they usually read actual SF or fantasy. People find them strange, dismiss them as impractical dreamers, or bully them.

All this is, if not like speculative fiction fans, at least like their self-images: Today geek culture is mainstream, but older fans still nurse grudges over lectures from teachers or bullying from peers about their then-weird obsessions. That’s why it’s a kick when a hero’s geek traits turn out to be superpowers. Science fiction geek heroes may be the only one who can solve a problem due to their ingenuity and special geeky knowledge. (Ernest Cline’s books are shameless examples.) Fantasy heroes either have honest-to-god magical powers connected to their imagination, intelligence, or love of reading, or are among the privileged few who can see magic or have access to portal or wainscot worlds.

At their smuggest, the lessons of flatter-the-fans stories are:

- Science fiction and fantasy are very special genres, and the fan culture surrounding them is also very special!

- Being, or at least resembling, a SF fan is a sign of intelligence and sensitivity!

I understand why sci-fi fans love this stuff–I can enjoy it, too, in the right mood. But I’m not sure stories telling fans they’re special are the stories they need right now. Again, these days stuff fans like is mainstream. Most pop culture caters to them already, and to the loudest, most aggrieved fans most of all.

Subtext #2: The Special People

Modern culture, geek culture especially, values people for what they are more than what they do. Sherlock Holmes has privilege but what makes him a hero are his skills, which theoretically anybody could learn with study. Contemporary pop culture heroes might be skilled, but they’re heroes because of powers or privileges nobody else can access. Our standard hero is the superhero. Superheroes are special because they’re aliens, or mutants, or just so rich they can build a batcave and train all day instead of getting a job. Even in a comic-book universe, any kid can’t grow up to be Superman.

It’s interesting watching existing characters evolve to fit the trend. The latest Star Wars protagonist, Rey, went from an impoverished nobody to the daughter of the emperor in two films (mostly because fans were loudly dissatisfied with the former option). The 1960s Captain Kirk was a man in his 30s who’d worked his way up through Starfleet; the new Captain Kirk is handed the Enterprise straight out of the academy. Doctor Who used to be a mediocre, underachieving Time Lord who fled Gallifrey out of boredom; now she’s an ex-super-spy whose superior alien genes are the original source of every Time Lord’s ability to regenerate. (And for a while now she’s been the last Time Lord in the universe, just to ensure no one has the authority to boss her around.)

The Part That’s Actually a Review of The Ten Thousand Doors of January

The Ten Thousand Doors of January is about January Scaller, a young woman at the dawn of the 20th century. January voraciously reads pulp novels and tales of adventure. (SF isn’t really a genre at this point, but she comes as close to fandom as she can–she even voluntarily reads Tom Swift books.) She can see doorways to other worlds. And she has the magical power to make things she writes come true, which she uses to open more doorways. She’s not just a fan; she’s become a writer herself, opening doors to worlds of her own.

So, yeah, The Ten Thousand Doors of January is wish fulfillment for fantasy readers. That’s no problem. I am a fantasy reader. And, honestly, The Ten Thousand Doors of January is an excellent novel of its type. I’m not saying it’s deep–it’s unambiguous, easy to interpret, and unlikely to confound or challenge most readers. As with a lot of SF, I get the sense this book is pitched younger than the adult audience it’s marketed to. Unlike a lot of SF, it feels like a novel, not a pitch for the Netflix series many writers seem to want instead. It’s a book about learning, uncovering information, more than presenting breathless action.

Its metaphors don’t work only one way; they rhyme with each other. It’s a novel about doors, and traveling between worlds, but January is also liminal herself: as an upper class mixed-race woman in 1900s America she moves between social worlds. January alone is perceived differently from January in the company of her wealthy white guardian.

We see a couple of worlds in detail, one independent world and one pocket-universe refuge for people marginalized by 1900s America. They’re both vivid. The larger world, a place of islands, tattoos, and word-magic, feels more distinctive and complete than most epic fantasy settings in a fraction of the space.

Ten Thousand Doors’ prose has style, not an attempt at styleless transparency. It’s sensitive to narrative voice, even down to the niceties of capitalization. As the novel begins it’s already asking us to notice the difference between a door and a Door. Which comes in handy, since the book has two narrators: January herself, and a nonfiction book on Doors that becomes a biography of Adelaide Larson, a woman who travels through them.

(That second strand sold me on the novel. Fantasy and science fiction don’t spend enough time exploring the worldbuilding and storytelling possibilities of fictional nonfiction. If nothing else it saves time when you can just come out and tell the reader about the world instead of implying everything through plot, and it’s often the more interesting option.)

And then–here’s where I start revealing the things that ought to surprise you on first reading–that biography neatly transitions into an autobiography of Yule Ian, its otherworldly author, then connects back to January’s plot, which loops around to the very beginning of the novel as she sits down to write, and then past it.

One of my cranky literary opinions is that every story has a narrator. Yes, even when they stick to close third person, or “transparent” style, the whole way through. You’re getting the characters’ thoughts and feelings because someone is telling you them. Sometimes this narrator is a persona the author wants to present to the audience. Sometimes it’s a persona the author doesn’t realize they’re presenting. One interesting question to ask about any novel is who is telling this story, and why? Even stories in first person don’t always consider the second half of that question.

Here, it’s easy to answer. Ten Thousand Doors is a first person narrative wedded to a mostly third person narrative that gradually lets the first person take over. Each narrator is writing to a specific audience for a specific reason.

Meanwhile the real-life readers are in the position of those characters, being addressed by the narratives. The nonfiction strand, addressed to January, ultimately explains her background and powers: you are magic. January’s story turns out to be addressed to an amnesiac boyfriend: an unsuspected magical girlfriend is looking for you. Both reinforce the book’s wish-fulfillment aspects.

On a higher level, both narrators are metaphorical fantasy authors–dreamers, writers, fascinated by Doors–making their cases for the importance of fantasy. But they do a weirdly lousy job of selling what’s so awesome about it.

Everybody Wants Their Genre to Rule the World

Doors are a metaphor for books. Speculative fiction, mostly; books about other worlds and presumably other possibilities.

Doors, The Ten Thousand Doors tells us, are also change. They’re the source of wonder and innovation, where revolutionary ideas slip into our world from fundamentally different ones: “revolution, resistance, empowerment, upheaval, invention, collapse, reformation—all the most vital components of human history, in short.”

The European rebellions of 1848 hung like gun smoke in the air; the sepoys of India could still taste mutiny on their tongues; women whispered and conspired, sewing banners and authoring pamphlets; freedmen stood unshackled in the bloodied light of their new nation. All the symptoms, in short, of a world still riddled with open doors.

Are they, though? There’s a step missing here: The Ten Thousand Doors never tells us what these changes have to do with Doors. It’s like the cartoon about the scientist who solves a complicated equation by writing “then a miracle occurs.” The book insists Doors are change but can’t come up with a concrete example of the world changing because of a Door.

You’ll notice these revolutionary movements happened in the real, Doorless, world. This is one of those fantasy stories set in the real world, which puts it in a bind. The novel can’t introduce changes that never happened or the world won’t look like ours anymore. It also can’t give Doors credit for real-world changes without denying credit to the real people who worked for them. True, a lot of social movements were in part inspired by books… but most of them weren’t the kind of books January reads. They were books like Das Kapital, or Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, or A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, or occasionally realist novels like Uncle Tom’s Cabin or The Jungle.

Mostly Doors aren’t about changing this world, but escaping into other ones. Adelaide finds Yule Ian’s world and her true love. January’s African governess slips into a world free from European colonialism. A community of outsiders and marginalized people take refuge on an uninhabited Earth. And there’s nothing wrong with this. Sometimes people need an escape, a refuge. Weird, bullied people, or those who’ve been genuinely marginalized: The Ten Thousand Doors makes sure to provide portals for the non-white, non-male readers who rarely got to star in the fantasies of decades past. This is all good!

It’s just that there’s a gap between what Ten Thousand Doors wants to make of fantasy and what it actually provides. It tells us stories can change the world, but only ever shows them leading people inwards to their own private worlds. In a way, Doors are change–but only for the select group of people who get to travel through them.

A Bad Witch

I might not have given The Ten Thousand Doors of January a shot if I’d remembered Harrow had also written “A Witch’s Guide to Escape: A Practical Compendium of Portal Fantasies,”. “A Witch’s Guide” has a similar central metaphor but isn’t as smart, or as kind. It’s one of the most obnoxiously smug flatter-the-fans stories I’ve ever come across. It still won a Hugo Award. That might be why it won a Hugo Award.

“A Witch’s Guide to Escape” is about a librarian/witch who sees her job as connecting people with The Right Book, or, as she puts it, “divining the unfilled spaces in their souls and filling them with stories and starshine.” I must emphasize here that at no point in this story is there any hint of irony.

You get a sense of the narrator’s personality when she says “There have only ever been two kinds of librarians in the history of the world: the prudish, bitter ones with lipstick running into the cracks around their lips who believe the books are their personal property and patrons are dangerous delinquents come to steal them; and witches.” She’s the kind of person who thinks there are two kinds of people. And, like a Josephine Tey character, she thinks she can know a person by looking at them. The patrons she’s concerned about are kids. She barely speaks to any of them, but brief glimpses as they pass through her library “kind of [tell] you all you need to know” about their lives. She knows what they need, and what they need is always the same thing. Fantasy, king of literature and the literature of kings!

“And you really can’t do anything for the people who only read Award-Winning Literature,” she says, “who wear elbow patches and equate the popularity of Twilight with the death of the American intellect; their hearts are too closed-up for the new or secret or undiscovered.” Which is amazing. I mean, if the internet has taught me one thing it’s that sci-fi/fantasy fandom includes some of the most incurious and unimaginative people on earth. And a lot of people they’d dismiss as “mundane” are smart, thoughtful readers. The narrator can’t imagine anyone might read “Award-Winning Literature” and find things in it that are new, or secret, or undiscovered. I read fantasy and Award-Winning Literature and off the top of my head I could come up with a half-dozen “literary” novels with more of the new and undiscovered in them than in Brandon Sanderson’s entire oeuvre.

A social worker brings one boy in and suggests he read some nonfiction about his depression instead of another fantasy novel. She’s not as diplomatic as I’d be, but she’s not wrong. I read fantasy, and I’ve dealt with depression. I need some escape sometimes but I can confirm nonfiction is better long-term help in this area than fiction of any genre. The witch is incensed: “Anyone could see that kid needed to run and keep running until he shed his own skin, until he clawed out of the choking darkness and unfurled his wings, precious and prisming in the light of some other world.” And, I mean… does she not realize it’s possible to read more than one thing? No, fantasy solves all problems! Fantasy is the most important literature.

So the witch steers kids to the books she thinks they need. It doesn’t work–one kid, pregnant and desperate, kills herself. So the witch swears she’ll give the boy one of the really magic books, the ones witches keep from the public. And she does, and it’s a literal portal, and the boy vanishes into it. The story says this is a happy ending. Maybe from the boy’s point of view it is. We don’t know. The witch is telling this story, and she’s so disengaged from the kids they barely have any dialogue; we never get his point of view. From everyone else’s POV, both he and the pregnant girl are equally gone from the world. What’s the difference?

But everyone else’s point of view doesn’t matter. The witch is a fantasy fan, “A Witch’s Guide” is here to tell us fantasy fans are wiser and more sensitive than the common herd.

Guarding the Doors

January’s guardian belongs to the New England Archaeological Society. The NEAS collects powerful artifacts from beyond the Doors. Then they close the Doors behind them so just anyone can’t do the same. The NEAS are special, better than the mundanes. They know what’s best.

The NEAS are SF fans. They’re the fans who police the boundaries, set pop quizzes to sort “real” fans from poseurs, and whine when their comic books start to look less white and male. They memorize canons and amass Funko pops while blockading the doors to divide themselves from the herd, keep the club exclusive. What kind of world would this be if January could get in?

But even a lot of fans on the right side of these fights, who want to open the doors, are more like the NEAS than they’d care to admit. January’s magical powers, remember, mark her as sensitive and creative. She’s a character the Witch from “A Witch’s Guide” might like to see herself in. The Witch is a speculative fiction fan, and she doesn’t want to keep anybody out–quite the opposite. But, well, some people are just too dead inside to get with the program, am I right? If they had any imagination they’d gladly be assimilated into her Borg. She won’t accept that people who love literature beyond fantasy could feel the same love for it or get the same rewards. Fantasy is her refuge. She can’t stand the suggestion that anything outside her fandom could be as important.

I’ve seen aggrieved SF fans set up psychological barricades to protect themselves from ideas that might pop their SF-is-special bubbles. They don’t consciously police boundaries, but they have the same combative grudge about other kinds of art that they imagine litfic readers have about SF. They get defensive over even mild criticism of the things they love. They question the imaginations of the non-genre readers, performatively sneer at the books they were assigned in high school, or dismiss litfic as books about professors having affairs with their students.

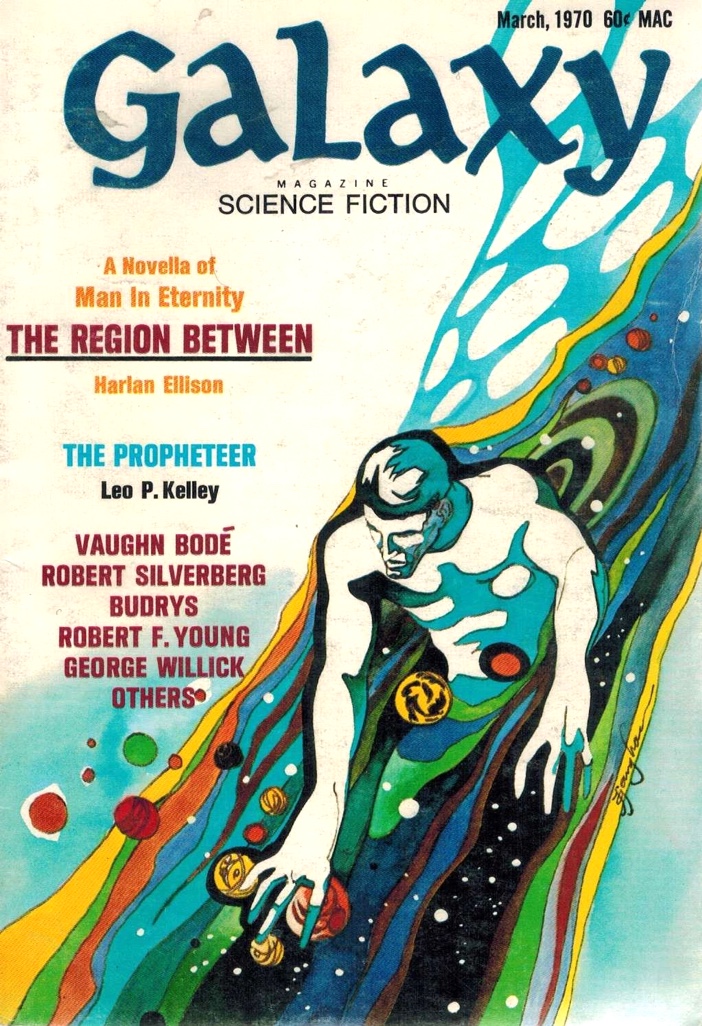

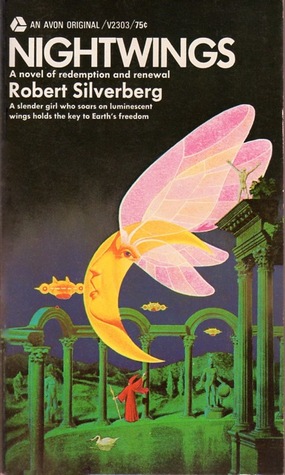

The result is that SF is so frustratingly small. From the golden age onwards, most popular writers have come out of the same fan culture and read the same books. Most SF draws from a limited range of styles, themes, and subjects. During the “golden age” we got pulp potboilers starring white, male soldiers and engineers. Today, the standard is a low-subtext Hollywood-style thriller. At all times, the style hasn’t strayed far from the contemporary understanding of “transparent prose.”

The core, non-small-press part of the speculative fiction genres don’t learn from anything outside themselves. If SF is so special and powerful, and its readers so especially imaginative and sensitive, what could the outside world have to teach?

Super Genres and Supermen

Alec Nevala-Lee’s brilliant book Astounding is part biography of Astounding Science Fiction editor John W. Campbell (along with Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and L. Ron Hubbard), part cultural history of his disproportionate impact on science fiction. Campbell was a man of strong opinions, most of them bad. He was convinced science fiction was not ordinary literature–it might even be the most important literature. He once told Barry Malzburg “There’s going to be a moon landing because of science fiction. There’s no argument.” By that point he’d spent his entire career trying to prove science fiction could change the world.

Campbell spent World War II looking for ways sci-fi might contribute to the war effort, imaging Astounding as a laboratory where smart people could brainstorm new ideas. He sometimes pitched schemes at actual government employee Robert Heinlein. Campbell was so desperate to prove his genre could lead to a world-changing breakthrough that after the war Hubbard suckered him into using Astounding to introduce Scientology.

Nevala-Lee writes Campbell saw Astounding as “an evolutionary collaboration between authors and fans to develop ideas at blinding speed… his ultimate goal was to create a new kind of person in both the magazine and its audience—a competent man who might pave the way for the superman to come.” Campbell wanted to be one of those competent men. He was a reasonably smart man who thought he was brilliant–the Dunning-Kruger Effect in human form. He’d grown up precocious, and bullied. The lesson Campbell took was that ordinary people can’t handle genius.

Science fiction of Campbell’s era was stocked with superhumans–people who were naturally smarter than the common folk. A. E. van Vogt’s Slan and Zenna Henderson’s People stories are famous examples. Campbell published Wilmar H. Shiras’s “In Hiding,” about a child psychologist who discovers a boy is hiding his true intelligence because the people around him Just Don’t Understand. The story consists of the kid explaining seriously and at length how smart he is–running selective breeding experiments with kittens, publishing stories in magazines whose editors don’t know he’s twelve. The boy isn’t just bright–normal people can’t educate themselves up to his level through hard work. He’s an atomic mutant, genetically superior. Brains are in his blood.

January, meanwhile, is special because she’s literally magic, and she’s magic because her father is from another world. January’s a better person than the NEAS, she’s not interested in excluding anyone, but she can’t help being special. The abilities that metaphorically mark her as a fan and a creator are hereditary powers no mundane human could learn. January masters them instinctively. They’re in her blood. She’s a superhero.

(Magic powers are often hereditary in fantasy. If you don’t want magic to be absolutely ubiquitous, restricting it to a small part of the population is an obvious solution. But it’s weird that it’s usually genetic. Why does it need to follow the rules of heredity? It’s magic.)

The significant, plot-moving characters in The Ten Thousand Doors are people who know about Doors. Few non-door-aware people get names. The novel cares about how they support or hinder January, or her parents or governess, or her enemies. It rarely hints at what goals they might have of their own. The Ten Thousand Doors of January is a struggle for control of fantasy fandom. Here, it’s the only world that matters.

One of the best small moments in The Ten Thousand Doors of January involves Adelaide’s journey to the island world. She needs a ship, and her Door is on top of a mountain, and she hires two Hispanic men to lug it up, and they’re the last people to see her before she disappears. And the book acknowledges the trouble this causes them! They’re not disregarded as extras–Adelaide’s biographer names and quotes one of them. We may not learn what January plans to do for the world outside her charmed Door-savvy circle, but this book knows January and her friends and family have responsibilities to others. The novel is calling Adelaide on her privilege–not just her white privilege, but her hero privilege.

The NEAS aren’t special–but neither are January and her parents. It’s easy to reject a villains’ assumption of specialness. Remembering to question a story’s assumptions about the hero’s specialness is harder. They usually aren’t conscious on the protagonist’s or the author’s part, so they’re more hidden.

Stories of special, magical people that lose this sense of perspective can be toxic. Heroes who are more special than everyone else aren’t held accountable for the collateral damage incurred by their adventures. Superhero movies often center the hero’s self-actualization while disregarding the background extras’ health and safety. They divide people into the special ones and the mundanes, and encourage the audience to identify with the special ones.

I know this post has rambled. I’m not sure it’s entirely cohered. But I do see points of connection between the gatekeeping fans; and the defensive, incurious fans; and stories about special people; and stories where those people are fans. The Ten Thousand Doors of January has the perspective and self-awareness they lack. On top of that, it’s genuinely well-written. Still, this book feels like a candy bar: I loved it, but I know if I consume too much of this stuff I’ll make myself sick.