1. The Surreal

All this is a digression and I do not wish anyone to think my mind wanders far, it wanders but never further than I want.

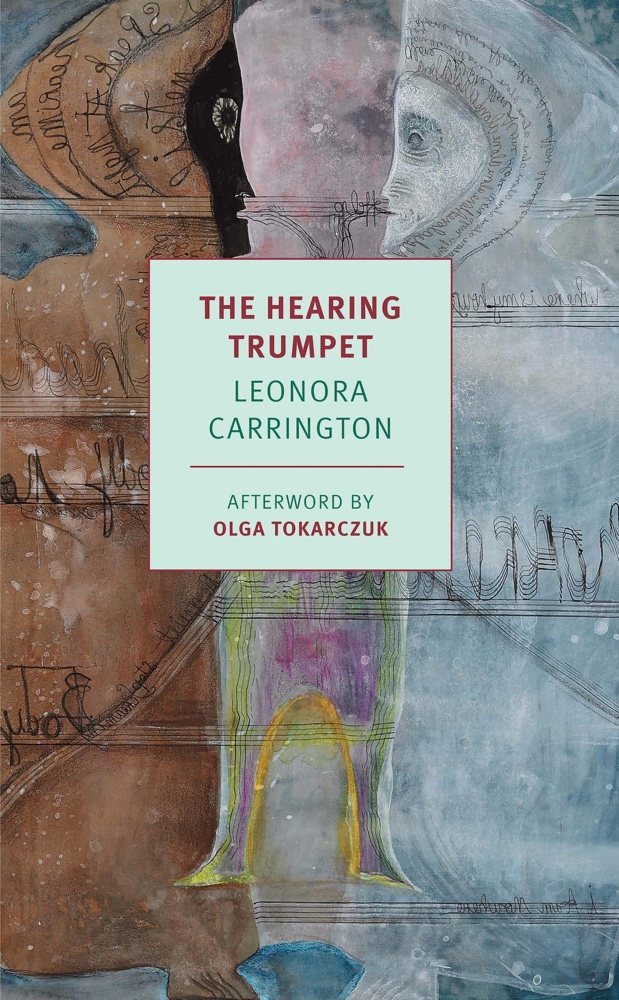

—Leonora Carrington, The Hearing Trumpet

The Hearing Trumpet isn’t about the hearing trumpet. That is, the trumpet doesn’t have a role in the plot; it’s just mentioned every so often. This is not Chekhov’s hearing trumpet. Still, Leonora Carrington’s novel kicks off with 92-year-old Marian Leatherby receiving the thing from her friend Carmella, so it’s important. Marian’s been given a way to extend her senses—far enough, Carmella suggests, to hear what others say while she’s out of the room.

I love Leonora Carrington’s stories but you want to read them one at a time. Most are heavily into dream logic and too many at once are too rich. I wondered how her style would work at novel length. But of course she adapted to fit the form: The Hearing Trumpet is a novel of escalating boiled-frog weirdness. It’s also both funny—the narrator has a lot of cockeyed opinions and the confidence to state them as fact—and genuinely uncanny. Reading it is like wandering through a slapstick dream.

It starts as (just barely) a realist novel. Marian lives with her son Galahad in Mexico. She keeps to herself and keeps busy. She sweeps out her room, has hilarious conversations with Carmella, saves cat hair to knit into a sweater, and dreams of traveling through Lapland by dogsled. Her self-assurance is vast. Is she growing a beard? Marian thinks it looks gallant, so what the hell. With age she’s stopped minding other people’s eccentricities or caring what they think of her own. In the afterward to the New York Review Books Classics edition, Olga Tokarczuk argues that old age is Marian’s license to be eccentric, fully herself, and frames The Hearing Trumpet as an argument for the revolutionary power of eccentricity, which she defines as a point of view “both provincial and marginal—pushed aside, to the fringes—and at the same time revelatory and revolutionary.”[1]

Marian narrates The Hearing Trumpet in the first person. She’s practical, and calm—absolutely unshakable. Never frightened; always amused, open, and curious. She grants all these qualities to the novel. So much of the feel of a novel hinges on the narrator’s personality. (And every novel has a narrator, even if it’s pretending not to!) Look at The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. It’s packed with events that would be grim in the straightforward, serious world of an Iain M. Banks novel. But Adams’ voice tells us not to panic. The Hearing Trumpet is a reassuring, optimistic book. But if Marian were anxious and unsettled, this would be an anxious, unsettling novel. It is, after all, a book about a woman committed to an institution where she’s subjected to a bizarre, overbearing treatment scheme.[2] The novel changes the emotional tenor of its plot by looking at it from an unexpected point of view.

2. The Surrealer

That’s the first thing Marian hears with her trumpet: Galahad and his family are putting her in a home. “People under seventy and over seven are very unreliable if they are not cats,” says Carmella. (Could Marian make Galahad into a sweater? I don’t think so.) The Institution of Dr. and Mrs. Gambit is a liminal place, the border between the real and the impossible. It could exist—within the laws of nature, I mean—but who’d build it? The elderly women warehoused there inhabit a bizarre jumble of novelty cottages: a shoe, a toadstool, a mummy case. Marian gets a miniature lighthouse she calls the Lookout. Again, she’s extending her senses. “Houses are really bodies,” says Marian, and during this out-of-body experience she’ll see and hear past the surface of the world.

The Gambits indoctrinate their charges in Inner Christianity, a vague regimen involving Movements, Self Remembering, and lots of Significant Capital Letters. Marian has free time to snoop, but can’t entirely escape the regimen—Dr. Gambit is intrusively audible even sans trumpet. Marian’s a vegetarian, used to directing her own diet. The Gambits let her stick to it but won’t give her a second helping of vegetables to make up for the lack of meat. The Institution isn’t adequately nourishing her. Still, she amuses herself by staring at a painting of a Winking Nun hanging opposite her chair. Somehow she intuits this person’s name was Doña Rosalinda Alvarez Cruz della Cueva. The painting has a hidden meaning. The castle housing the Institution holds secrets Dr. Gambit is unaware of, brought over from Spain by a refugee during their Civil War. Something lives in its tower.

Sometimes talking about the genre of a book in broad terms (like Science Fiction or Horror) is less interesting than treating a specific thing the work is doing as its own subgenre, and finding other, sometimes unexpected works that relate to it as a result. The Hearing Trumpet reminds me of Twin Peaks and Philip K. Dick’s VALIS that way, though in other ways they don’t resemble each other at all. They’re all metaphysical investigations: characters peel back layer after layer of their apparently ordinary world to discover unexpectedly idiosyncratic metaphysics. These stories often use existing mythology as a springboard. The Hearing Trumpet brings in the Holy Grail, as well as a lot of Gnostic ideas I’m not informed enough to comment on. But these are only starting points for more personal mythologies.

The mythology of The Hearing Trumpet centers around the Grail, really a pre-Christian artifact coopted by the Church: the cup of the goddess Venus, meant to hold Pneuma, or life-essence. It also takes in bees, werewolves, Taliesin, the Pole Star, soup, and the life of the Abbess Doña Rosalinda Alvarez Cruz della Cueva, who attempted to rescue the Grail from the Knights Templar. This is a book within a book—dozens of pages narrated by a medieval chronicler—provided by Christabel, a mysteriously busy resident who claims to be twice as old as Marian and guards the Abbess’ legacy.

If you’ve read Tim Powers this might sound like the kind of thing he gets up to—setting up a mythological shadow world behind ordinary reality. But there’s a difference that points to why The Hearing Trumpet, or VALIS, or David Lynch feel specifically surreal as opposed to fantastic. Powers’ novels are about specific worldbuilding. The fun is in watching the characters figure out exactly how their world works and how they can work within it. But surreal metaphysics are never completely known. They’re not logically worked out jigsaw-puzzle worldbuilding, but a line into another person’s subconscious. Some of the resonances of their symbols are only fully understood by the author, or the narrator—assuming they fully understand it themselves. Not all questions will be answered, no matter how deep the protagonist digs. The world never loses its mystery.[3] Its systems remain open—you can interpret and reinterpret them forever. These stories aren’t bothered about whether the audience understands everything they’re getting at. They’re not bothered if you understand something else—some meaning from the margins, personal to you.

3. The Surrealiest

Back in the present, two women who are really into Inner Christianity and aligned with the Gambits poison a fellow inmate.[4] This drives the other women to band together and declare a hunger strike until the poisoners are expelled. They feed themselves only from their own resources (for now, mostly a store of chocolate biscuits). As the Gambits lose control, the weather turns mysteriously cold. The world has turned on its side and the poles have migrated to the equator. The margins have replaced the center.

When the world tips over the cause-and-effect narrative (Marian embarrasses her family, therefore they put her in a home) tips over into full surrealism. Now things are happening just because it feels right for them to happen in that moment. The women’s revolution coincides with a revolution of the earth. Christabel emerges as a leader, challenging Marian with riddles and introducing the women to the local bee-goddess. Marian’s friends start turning up: Carmella digs a tunnel to the Institution to bust Marian out, hits uranium instead, and gets rich enough to supply the women with whatever they need. A European friend brings a tribe of werewolves in an atomic ark. The elderly women build an anarchic society of their own in the ruins of the Institution.

“It is impossible to understand how millions and millions of people all obey a sickly collection of gentlemen that call themselves ‘Government!’ The word, I expect, frightens people. It is a form of planetary hypnosis, and very unhealthy."

“It has been going on for years,” I said. “And it only occurred to relatively few to disobey and make what they call revolutions. If they won their revolutions, which they occasionally did, they made more governments, sometimes more cruel and stupid than the last.”

“Men are very difficult to understand,” said Carmella. “Let’s hope they all freeze to death.”

This is, I must admit, one of those stories where the protagonist is empowered by an apocalypse. This isn’t a plot I care for when handled realistically. But this is an openly metaphorical apocalypse. Marian’s inner journey is manifesting itself in the world; her inner world and outer world grow more numinous in tandem. Finally Marian descends beneath the tower and meets herself making soup in a cauldron. She jumps into the pot and the Marians converge, at once being the soup and eating it. Food in this novel is a stand-in for everything that feeds Marian’s mind and soul. She’s self-fueling, feeding her soul from her own resources.

At this point the women retrieve the grail in a full-scale assault on its captors—but it’s an epilogue. It happens very fast and, as it were, offstage. Which isn’t how a typical book would work: isn’t this the exciting part? But once Marian’s gone through her evolution, in a sense she has the Grail already; getting the literal plot-Grail is just confirmation. Again, by this point in the book plot logic has slipped out the back door and run halfway to Canada; things are happening because they feel right.

If too many books worked like this it might get old, but occasionally it makes a nice change. The culture of the 21st century is dominated by TV and film, which in the U.S. means mostly Hollywood. They account for most of what most people consume and their conventions filter out into other media. And our stories are so… let’s say, engineered. Our culture prefers a narrow range of structures and story-types. It’s not like there aren’t good reasons for that; three-act structures and heavily codified writing advice can serve as useful guard rails. It’s easy for weirdly structured or unstructured stories to just not work. But an artistic ecosystem needs mutants. Stories that are weird, baffling, ambiguous, mulishly stubborn, frustrating the audience’s expectations. Works that carve out new ecological niches, off to the sides, expand the range of possibilities for everyone else. This is where surrealism can come in handy.

Marian narrates the beginning of the novel, where she describes life with her son, and the end of the novel, where she describes life in the new world, in the present tense, but the story in between is in past tense. Marian starts out in a pleasant state of present-tense equilibrium and seems to enter into history as her problems begin. Now she’s emerged again into a new open-ended present. By the end of the novel she’s ready to ride through the newly snowy landscape on a sledge pulled by wooly dogs. She’s creating her dreams where she is.

-

I recommend reading Tokarczuk’s afterword, reprinted at that link; honestly, it’s a better reading of the novel than mine could be. She talks about the value of “openness” and “wild metaphysics” in fiction, and when I read that I thought: yes, that’s what I’m looking for these days. ↩

-

For a more serious though still brave version of this story, see Carrington’s memoir Down Below. ↩

-

The Jamesian ghost story is a close relative, although its key emotion is fear instead of wonder. It has the investigation, the openness/incompleteness, the hints of more to the workings of the world. ↩

-

It might be relevant for some readers that The Hearing Trumpet features a depiction of a transgender woman that seems well intentioned for the mid–1970s but might feel dated. First, she’s also the only character who dies. Second, the characters don’t seem entirely clear on whether she’s trans or living in disguise to stay near a lover, or aware there’s a distinction. But the novel makes it clear she belongs with the other women—at one point she has a dream that indicates she’s being invited into the same mysteries as Marian. ↩