(I’ve been reading the stories that got both Hugo and Nebula nominations. To see all the posts in the series, check the “Joint SFF Nominations” tag.)

Last time, in 1967, we saw the SFF world give awards to aesthetically and politically conservative stories. But the New Wave hadn’t gone anywhere. In his essay “Racism and Science Fiction,” Samuel R. Delany recalls at the following year’s Nebula awards an “eminent member of SFWA” gave a speech fulminating against “pretentious literary nonsense.” (The proximate cause of the speech was apparently Delany’s Nebula-nominated The Einstein Intersection, which the speaker had heard described but had not read; when he did he was taken aback to discover he liked it.) There’s still a tug-of-war between SFF’s pulp roots and its avant garde, and we’re about to see the rope pulled back in the other direction in the awards of:

1968

In 1968, four novels scored nominations for both the Hugos and the Nebulas: Samuel R. Delany’s The Einstein Intersection, Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light, Piers Anthony’s Chthon, and Robert Silverberg’s Thorns. The Delany won the Nebula and the Zelazny won the Hugo. Those two novels are still remembered and read; the other two not so much.

These are the short stories, novellas, and novelettes nominated for both awards:

- Samuel R. Delany, “Aye, and Gomorrah” (Won the Nebula for Best Short Story): An astronaut between trips doesn’t quite connect with a woman.

- Harlan Ellison, “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes”: A gambler encounters a slot machine possessed by a woman who died playing it, who promises him jackpots.

- Philip José Farmer, “Riders of the Purple Wage” (Tied for the Hugo for Best Novella): An artist prepares for his latest exhibition in an age of universal basic income. Puns ensue.

- Fritz Leiber, “Gonna Roll the Bones” (Won both the Hugo and Nebula for Best Novelette): A gambler gets into a high stakes craps game, bites off more than he can chew, and barely escapes with his skin.

- Anne McCaffrey, “Weyr Search” (Tied for the Hugo for Best Novella): On a medieval planet, dragon riders visit a castle looking for more people to ride dragons.

- Robert Silverberg, “Hawksbill Station”: A few days in the life of political prisoners marooned in the Cambrian era by a time-traveling government.

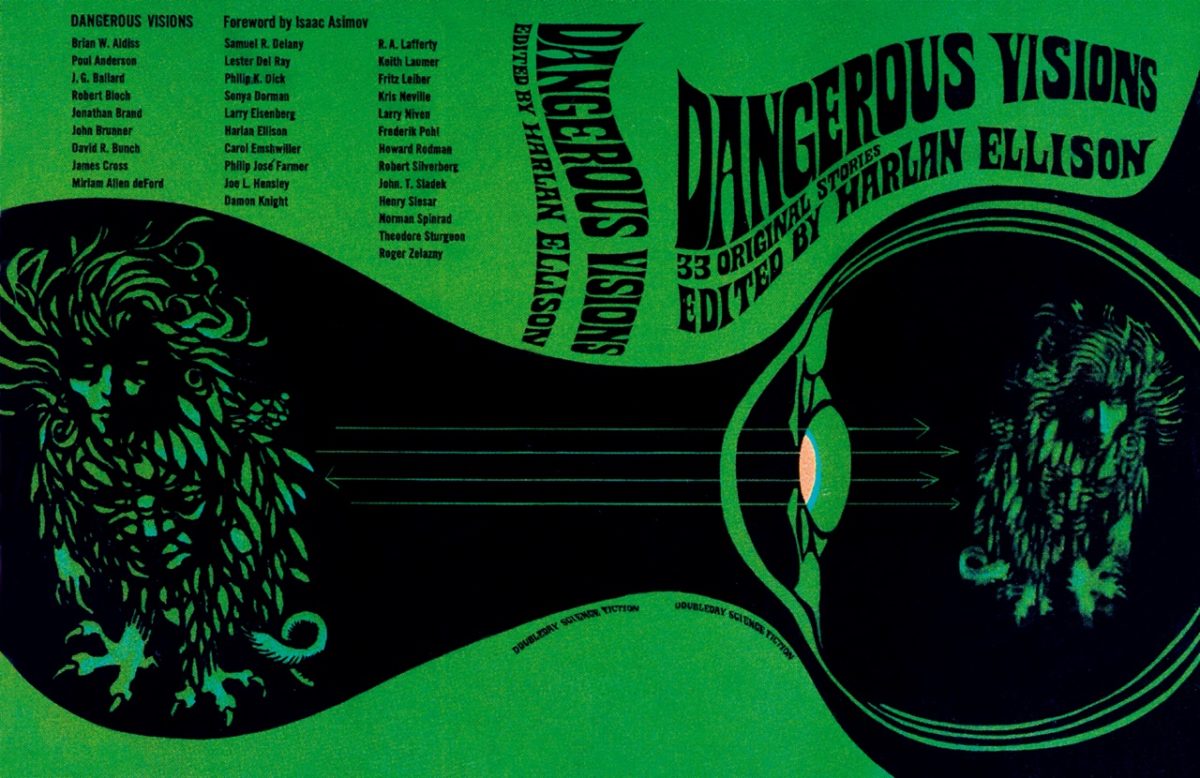

The big theme for 1968 is Dangerous Visions. This was a massive anthology edited by Harlan Ellison (the author of “Repent Harlequin, Said the Ticktockman”). “Aye, and Gomorrah,” “Riders of the Purple Wage,” and “Gonna Roll the Bones” were first published there. All three won at least one award. “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes” was published elsewhere but written by Ellison, the anthology’s editor and chief creative influence, so it shares a sensibility. Three more stories from Dangerous Visions received either Hugo or Nebula nominations. Philip K. Dick’s “Faith of Our Fathers” and Larry Niven’s “The Jigsaw Man” turned up on the Hugo ballot, and a Nebula nomination (bizarrely) went to Theodore Sturgeon’s “If All Men Were Brothers, Would You Let One Marry Your Sister?”

Before I get into Dangerous Visions, though, let’s deal with the two stories about which I have the least to say: “Weyr Search” and “Hawksbill Station.”

Safe Visions

It says nothing good about the SFF world in the sixties that, three posts in, Anne McCaffrey is only the first woman we’ve covered. One of her stories will fall into our Venn diagram for three years straight; then she drops out of the story. Why everyone was briefly excited over McCaffrey isn’t clear. “Weyr Search” is a pulp adventure story indistinguishable in quality or style from any number of others now forgotten. The prose is bland and sometimes descends into clumsiness. (“This, then, is a tale of legends disbelieved and their restoration. Yet—how goes a legend? When is myth?” When is myth what?) Characters have names like F’Lar, F’Nor, and Fax. I assume “Weyr Search” stood out because in the sixties there weren’t many stories for dragon lovers—as discussed last time, this is another epic fantasy under a science fiction veneer. It’s technically also a story with a female protagonist—again, rare in 1968—but in practice most of the story is told from the POV of F’Lar (or was it F’Nor?).

We’re going to be seeing a lot of Robert Silverberg for a while. At any given time a few writers show up on SFF awards lists over and over for several years, after which they drop off for new favorites.[1] We’re already seeing Harlan Ellison come up a lot; future favorites will include George R. R. Martin, Orson Scott Card, Connie Willis, and Mike Resnick. Here I’ll admit my biases: Ellison’s fine, but these are usually writers I’m not into. It feels like they please crowds not because their stories are great, but because there’s nothing in them to put anyone off. They’re not bad, just beige. Their work feels like a rainy Sunday morning when someone is watching a fishing program on TV in the next room. Silverberg is one of those.

“Hawksbill Station” is a perfectly good story. It’s a solid character piece with no real flaws. Silverberg writes good prose. It just feels a bit thin. The first thing we read is “Barrett was the uncrowned King of Hawksbill Station.” When he learns he could return to the future but chooses to stay, nothing about his decision is a surprise. Silverberg later expanded “Hawksbill Station” into a novel and it may have made Barrett’s motives more complex, but in the novella it just feels like he wants to be a big trilobite in a small pond.

Dangerous Visions

So, Dangerous Visions. Like I said, this was a big deal. Partly this is because non-reprint anthologies were unusual at the time (although by this point Damon Knight’s series Orbit had started up), and this was a big one full of major writers. But Ellison had bigger ambitions: He kicks off the book by proclaiming “What you hold in your hands is more than a book. If we are lucky, it is a revolution.” Ellison was prone to hyperbole the way fish are prone to swimming, but he really was taking this seriously: he sunk $2700 of his own money into the project (according the online inflation calculator at the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, over $20,000 today) and borrowed another $750 from Larry Niven.

So what was revolutionary about Dangerous Visions? Ellison had a couple of goals. One was to publish strong and even experimental writing styles in a genre that too often defaulted to “transparent prose.” The other was there in the title: Ellison wanted “dangerous,” taboo-breaking stories. In his introduction Ellison argues a SFF writer’s work is “precensored even before he writes it” because most editors started as fans, and deep down in their subconscious what they really wanted was stuff like the stories they grew up with. So they wouldn’t buy literary styles, or stories with sex or (certain kinds of) politics. Ellison wanted radical stories. Stories that tore walls down and busted doors open. Stories no one else would buy because they were too mind-blowing.

How this worked out in practice…

Secretions

One way to asses the strengths and weaknesses of Dangerous Visions might be to look at “Riders of the Purple Wage.” Of all the stories in Dangerous Visions, “Riders” is both the longest and the most… well, the most.

At one point in “Riders” an art critic declares “every artist, great or not, produces art that is, first, secretion, unique to himself, then excretion. Excretion in the original sense of ”˜sifting out.’ … The valor comes from the courage of the artist in showing his inner products to the public.” And man is Philip Jose Farmer not afraid to show us his inner products. He’s one of those SFF writers who feel like outsider artists. I’ve read the Riverworld series and the first of his World of Tiers books. In the former he excitedly plays with historical figures like a kid smashing his action figures together; the latter feels like he brain-dumped his weirdest daydreams onto the page. Whatever else I think of Farmer’s writing, I have to admit he writes what he damn well pleases.

“Riders” follows Chib Winnegan as he prepares his latest painting for an exhibition. It’s 2166 and most people live on a universal basic income, the “purple wage.” Meanwhile, Chib’s Heinleinesque great-grandfather watches the world through a periscope and editorializes. As an exercise in style, it’s amazing. It’s a delirious slapstick picaresque, fast-paced and as packed with baroque detail as a Hieronymus Bosch painting. It’s in love with wordplay: there’s a pun every few lines. For several pages a psychiatrist analyzes Chib and his artists’ group, the Young Radishes, through etymological free-association. Farmer is no James Joyce but he’s under Joyce’s influence here, as acknowledged in the story’s climactic pun. Focus on the prose, grab hold of form and let content go, and parts of “Riders” are enormous fun.

That content, though. Farmer opens with an off-putting sex dream in which Chib imagines himself as a giant phallus. If you make it through this first chapter you’ll find it sets the tone. Chib’s mother is enormously fat and it’s a cue to read her as a grotesque. One of her friends urinates in her living room because the “sprayers” will clean it up. White dropouts change their names and live in the forests as pretend Native Americans. 22nd century Earth has legalized incest. One allegedly “funny” scene involves a sexual assault and the discharge of an entire can of spermicidal foam in someone’s living room. This was the first time I’d read “Riders”—I read a lot of Dangerous Visions years ago, but not every story—and I cringed on every page. This isn’t just values dissonance between a fifty year old story and my 21st century sensibilities. Farmer is out to shock.

Here’s something else that happened in early 1968, around the time SFF fans and writers were deciding what stories from 1967 were most award-worthy: The first issue of Zap Comix came out.

Zap kicked off the underground comics movement. It wasn’t the first underground comic (that was probably Frank Stack’s The Adventures of Jesus, although some online histories cite Jack Jackson’s God Nose). But Zap was the most famous and most of what was to come was either modeled on or reacting against it. If you’re not familiar with underground comics, first recall that in the sixties comics were aimed at children and their content was governed by the Comics Code Authority. The CCA was a Hays Code for comics, private self-censorship guidelines instituted by comics publishers hoping to dodge government censorship after Congress freaked out over E.C.’s gory horror comics. The undergrounds were small-press satirical comics aimed at adults and not bound by the CCA. They tended towards the surreal and often threw rapid-fire random crap together like Farmer in “Riders of the Purple Wage.” In the pages of Zap, cartoonists like Robert Crumb, Victor Moscoso, Spain Rodriguez, and S. Clay Wilson could express themselves freely and explore any themes they chose.

The results… well, Jeff Goldblum has a line in Jurassic Park: “Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.” If you can focus on style and ignore the content, a lot of Zap is amazing to look at. I love Moscoso’s style and Crumb’s draftsmanship skills are genuinely great. But you can’t ignore the content. The underground cartoonists were so drunk with the opportunity to draw anything they plunged right into drawing the most taboo-breaking things they could come up with. And breaking taboos, it turns out, is not inherently courageous. Mostly the underground cartoonists drew images they should never have let out of their heads: racist caricatures, creepy sex, huge genitals, sadistic violence, and misogyny. So much misogyny. If you have any taste at all, Zap is unreadable.

Dangerous Visions is science fiction’s underground comics. Not that it’s unreadable. Some of these stories are good. Some are real classics, including “Faith of Our Fathers” and “Aye, and Gomorrah.” But where Dangerous Visions fails, it fails like Zap. We’ve already discussed Farmer’s story. Ellison’s own story described killings by Jack the Ripper in too much detail. Robert Silverberg wrote about an astronaut torturing his old girlfriends. Miriam Allen deFord’s “The Malley System” is little more than an excuse to describe brutal murders from the murderers’ perspectives. Henry Slesar’s “Ersatz” is a joke with a transphobic punchline. The prize for most inadvisable story has to go to Theodore Sturgeon, who must have taken Ellison’s invitation as a challenge to come up with the worst thing he could think of. This was the incest-promoting “If All Men Were Brothers, Would You Let One Marry Your Sister,” a story utterly inexplicable except maybe as the most tasteless possible parody of Robert Heinlein in lecture mode.[2]

Invited to write “dangerously,” writers defaulted to “edgy”—Unpleasant sex! Gore! Cannibalism! Misogyny! Also, maybe religion is bad! Am I blowing your tiny minds? There weren’t many actual taboos in SFF by the late sixties. Most of the ones Dangerous Visions could find were taboos for good reason—say, the taboo against starting a story with a giant slithering penis, which was just saving writers from themselves. The taboos that need busting aren’t the ones that make people say “eww, yuck” when you break them. They’re the thoughts you don’t notice you’re not thinking. For instance, let’s return to the Samuel R. Delany essay I linked at the top of the post and look at something else that happened to Delany in 1968:

"Three months after the awards banquet, in June, when it was done, with that first Nebula under my belt, I submitted Nova for serialization to the famous sf editor of Analog Magazine, John W. Campbell, Jr. Campbell rejected it, with a note and phone call to my agent explaining that he didn’t feel his readership would be able to relate to a black main character.

[…]

It was all handled as though I’d just happened to have dressed my main character in a purple brocade dinner jacket. (In the phone call Campbell made it fairly clear that this was his only reason for rejecting the book. Otherwise, he rather liked it… .) Purple brocade just wasn’t big with the buyers that season. Sorry… . "

Among the things you didn’t see much of in sixties SF—even the progressive kind—were stories that didn’t treat whiteness as the default state of humanity, and stories about worlds without misogyny.[3] But it didn’t occur to anyone that these were taboos, or that they could break them. Dangerous Visions wasn’t dangerous in any way that mattered.

And Yet: Style!

On the other hand, that goal of publishing stories with style? Complete success. The best stories in Dangerous Visions (and they’re generally the least taboo-breaking stories) are just fun to read. Take “Gonna Roll the Bones,” which begins like it’s exploding:

Suddenly Joe Slattermill knew for sure he’d have to get out quick or else blow his top and knock out with the shrapnel of his skull the props and patches holding up his decaying home, that was like a house of big wooden and plaster and wallpaper cards except for the huge fireplace and ovens and chimney across the kitchen from him.

There’s a rhythm running all the way through the story, spiced with long sentences patched together with commas and conjunctions that seem to tumble to a stop like rolling dice: “Then he threw back his shoulders and grinned his lips sneeringly and pushed through the swinging doors as if giving a foe the straight-armed heel of his palm.” “As Joe lowered his gaze all the way and looked directly down, his eyes barely over the table, he got the crazy notion that it went down all the way through the world, so that the diamonds were the stars on the other side, visible despite the sunlight there, just as Joe was always able to see the stars by day up the shaft of the mine he worked in, and so that if a cleaned-out gambler, dizzy with defeat, toppled forward into it, he’d fall forever, toward the bottommost bottom, be it Hell or some black galaxy.” It’s propulsive, like the story is pushing you forwards, and hard not to keep reading. Fritz Leiber modeled “Gonna Roll the Bones” on tall tales and the narration sounds like a storyteller, a rough one who rambles a bit and can’t get the words out fast enough when he’s excited.

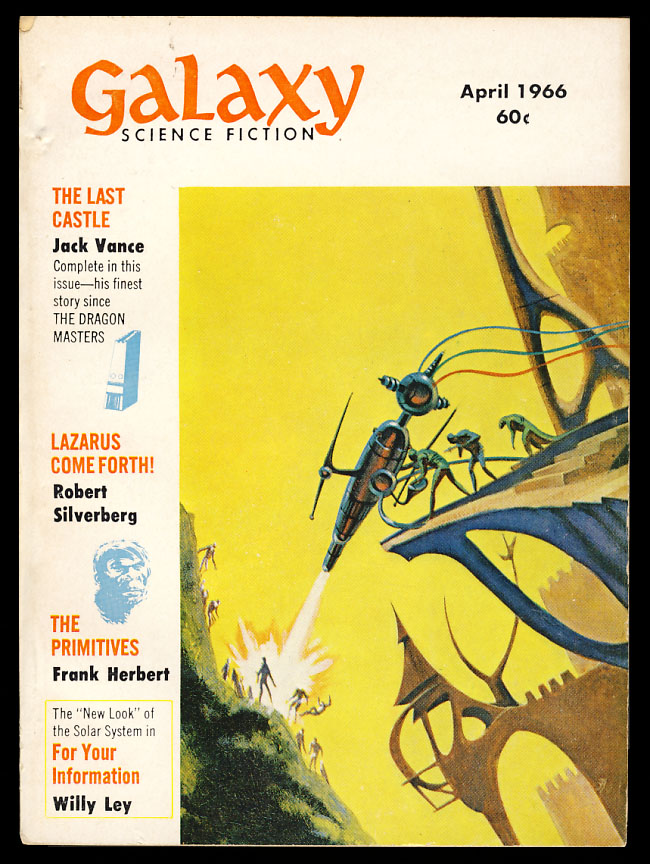

Interestingly, “Gonna Roll the Bones” looks almost exactly like the American south in the early 20th century but casually mentions spaceships as just a normal thing. Like “Weyr Search” or last year’s “The Last Castle,” this is another future that looks like the past—but it feels odder, because it’s not emulating a Tolkien-style fantasy world. It’s like Lieber wasn’t sure a Twilight Zone-style story would fit Dangerous Visions without a science fiction veneer.

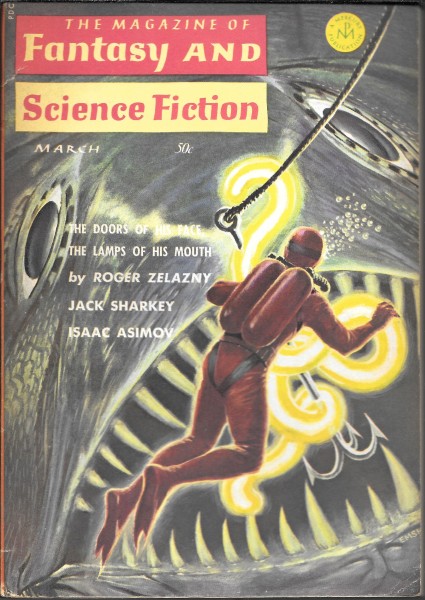

You’ll excuse me if I bring “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes” in here. Again, this is not a Dangerous Visions story, but it’s an Ellison story and feels of a piece with his editing work. And, like “Gonna Roll the Bones,” this is another story about a gambler in over his head, which after Dangerous Visions itself is the most obvious thematic link between any of these six stories. It’s written in multiple styles, straight third person for present-day scenes, fast-moving, impressionistic italics when it flashes back to Maggie’s biography. As this strand closes in on Maggie’s death it dips into her stream of consciousness, putting us directly in her head. For a page the story turns into concrete poetry: a short funnel of text, then sentence fragments broken by black bars like pinball bumpers, falling into to a cramped text box as the machine traps her soul.

In “Bones” gambling is risk-taking; in “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes” it’s addiction, obsession. Our protagonist, Kostner, watches a fellow gambler mechanically feed coin after coin into the slots, “almost automated.” She animates only to glare at a winner; she’s gambling to fill some hole—maybe chasing the freedom money brings—and resents the winner having something she can’t. Mediocre SFF often doesn’t try to set up patterns of imagery. “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes” is one model of how to do it. Kostner gets more numb the more he wins. The pit boss’s grin is “conditioned reflexes,” the floor manager’s eyes “held nothing of light,” the casino owner’s smile seems “stamped on him.” Maggie is “An operable woman, a working mechanism,” she’s objectified in that men treat her as their object, in the sense of an objective. A goal, a prize. Las Vegas is part of a system that reduces everyone it touches to things, machines for wanting.

In the section on underground comics I mentioned there’s an undercurrent of misogyny running under some of these stories and it’s detectible in “Gonna Roll the Bones” and “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes.” But in each story it’s of a different kind. In “Gonna Roll the Bones,” the misogyny is Joe’s; the narrative just doesn’t judge it because it’s in his head. This is a point contemporary readers might stumble over. These days SFF fans expect protagonists to be heroes, characters to identify with. Outside of SFF, that’s not always how it works. Joe’s an abusive lout; we don’t identify with him, we’re just interested in him. Specifically, we’re interested in seeing him humbled. Which he is—Joe’s in a good mood as the story ends but he’s not in the mood to go home, which from his wife’s perspective has got to be a win.

The problem is “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes” has a touch of misogyny running not through a character but through the story itself. I think it’s unintentional. The story flashes back to Maggie’s life and into her head because it wants us to know she doesn’t act out of malice, just self-defense. Men have not been her allies. But it also relays Maggie’s life with more than a hint of condescension (“operable,” a “mechanism”), and in the end, with Kostner taking Maggie’s place in the machine, this is the story of a hapless schlub stabbed in the back by a seductive femme fatale. This story has empathy for Maggie, but parts of it push back against the work it does to humanize her.

Don’t Mention the War

In June of 1968 a pair of ads appeared on facing pages of Galaxy magazine. One read “We the undersigned believe the United States must remain in Vietnam to fulfill its responsibilities to the people of that country,” followed by a list of names that included Poul Anderson, Jack Vance, Larry Niven, Robert A. Heinlein, and John W. Campbell. The other read “We oppose the participation of the United States in the War in Vietnam,” followed by a list including Samuel R. Delany, Harlan Ellison, Philip Jose Farmer, Fritz Leiber, Robert Silverberg, Isaac Asimov, and Ursula K. LeGuin. Kate Wilhelm and Judith Merril organized the anti-war petition; Poul Anderson put the pro-war petition together in response.

There are a couple of things to notice here. First, the anti-war side has an infinitely better pool of writers. It includes not only almost all our award nominees (Anne McCaffrey didn’t sign either statement) but other great writers both famous (Ray Bradbury, Peter Beagle) and underrated (Margaret St. Clair, Sonya Dorman.) The only serious talent on the other side is R. A. Lafferty.[4]

More relevantly, the Vietnam war was by this point arguably the most all-consuming political issue in the United States, and SFF writers were as engaged with it as anyone else. So it’s interesting the double-nominated stories that year… well, aren’t. Maybe the two sides cancelled each other out in voting?

“Hawksbill Station” feels political but the politics are background scenery in a story about something else. Here we have communists imprisoned by a right-wing government, but you could tell the same story with the roles reversed. Being heavily into feudalism is about as far as the politics of “Weyr Search” go. “Aye, and Gomorrah” wants to broaden SFF fans’ outlook on gender and sexuality, and “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes” touches on capitalism and inequality.

The most topical story is “Riders of the Purple Wage,” though the current event Farmer is riffing off of has been forgotten. In 1964 a group of activists and academics calling themselves “The Ad Hoc Committee on the Triple Revolution” wrote a memo called “The Triple Revolution,” which they sent to President Lyndon Johnson. The committee was concerned with nuclear proliferation and civil rights, but the main thrust of the memo was about what they called the “Cybernation Revolution.” They believed increased automation would lead to increased unemployment or underemployment, and serious economic inequality (and, honestly, I can’t say they were wrong). The committee had immediate suggestions for dealing with this but their long-term hope was that the U.S. would institute what we now call a universal basic income.

It’s not clear whether Johnson ever got the memo, but it impressed Philip Jose Farmer. In his Dangerous Visions afterward Farmer enthuses, “this document may be a dating point for historians, a convenient pinpointing to indicate when the new era of ‘planned societies’ began. It may take a place alongside such important documents as the Magna Carta, Declaration of Independence, Communist Manifesto, etc.” In his guest of honor speech at the 1968 World Science Fiction Convention, Farmer even called on fans to form a nonprofit organization, to be called REAP, to promote the aims of the Triple Revolution committee, pointing out that earlier that year fans had organized to keep Star Trek on the air.[5] He was disappointed when no one took him up on the offer.

But the story’s politics are muddled. Farmer agrees a basic income would be a good idea. At the same time, “Riders of the Purple Wage” argues most people don’t have great unrealized talents: “They believed that all men have equal potentialities in developing artistic tendencies, that all could busy themselves with arts, crafts, and hobbies or education for education’s sake. They wouldn’t face the ”˜undemocratic’ reality that only about ten per cent of the population—if that—are inherently capable of producing anything worth while, or even mildly interesting, in the arts.” Most people in Farmer’s story sit around watching TV. Farmer can’t quite imagine a science fiction story without someone to sneer at.

“Aye, and Gomorrah”

The one story we haven’t touched on is “Aye, and Gomorrah.” I first came across it in David G. Hartwell’s World Treasury of Science Fiction.[6] I was 12. I don’t recall my reaction to “Aye, and Gomorrah” but I’m sure I didn’t understand a word of it.

Its first words are “And came down in Paris,” and anytime the first word of a story is “And” you know you’re starting in the middle of something that’s been going on a while. Scenes are punctuated by regular repetitions of “And went up” and “And came down,” and the story ends in an “And went up” to match the initial descent. This is a regular pattern in the narrator’s life, and it feels circular.

We’re dropped in without context. A common worldbuilding technique in SFF is to avoid directly explaining the world, instead writing from an in-world perspective and letting the reader piece it together from the clues. “Aye, and Gomorrah” uses this tactic but doesn’t give us enough information to orient ourselves until mid-story—we’re off balance, out of our element, just as the narrator is out of their element on Earth. They’re a Spacer, an astronaut, and Spacers are something apart: people dismiss them with an oddly ritualistic “Don’t you… people think you should leave,” pausing like they need to search for the word people.

The narrator meets a gay man in France, and he thinks they might once have been a man. They meet a prostitute in Mexico, and she thinks they might once have been a woman. They are apparently neither. They ask both man and woman whether they’re a “frelk.” Spacers have frelks on the brain. Is this person a frelk? How about those guys? Where are the frelks? In Istanbul the narrator meets a frelk and their conversation gives us the context we were missing. In space radiation does a number on your gonads, so Spacers are neutered; this leaves them asexual and they’re considered non-gendered. “Frelk” is slang for people attracted to Spacers. They’re attracted to people who won’t be attracted back in the same way. Most Frelks pick up Spacers surreptitiously and pay for their favors.

Samuel R. Delany is a gay man in the late sixties writing about people whose affections and gender identities aren’t recognized as legitimate. He’s communicating the feel of this by translating it into a situation less threatening to an audience immersed in casual homophobia. Something that’s worth noting here—and I’m not at all the first person to notice this, see for example this post at the British Science Fiction Association’s blog Vector—is how the frelk decorates her apartment: “Marsscapes! Moonscapes! On her easel was a six-foot canvas showing the sunrise flaring on a crater’s rim! There were copies of the original Observer pictures of the moon pinned to the wall, and pictures of every smooth-faced general in the International Spacer Corps.” If science fiction readers responded to “Aye, and Gomorrah,” maybe it’s partly because it treats SF fandom as a sexuality.

More broadly, this is also a story about two people failing to connect. The frelk wants to make a real emotional bond with the Spacer but she’s also exoticizing them (“You spin in the sky, the world spins under you, and you step from land to land”). She can’t make a real connection to a romanticized version of the person she’s trying to connect with. And the Spacer refuses to believe the frelk might not see this relationship as transactional. And it’s all depicted with empathy for both sides.

That’s what makes “Aye, and Gomorrah” a classic. It’s a story of miscommunication and awkwardness, but written with compassion and genuine affection for humanity. Delany actually seems to like people. “Aye, and Gomorrah” is the last story in Dangerous Visions and coming after a volume of cynical, often edgy stories this is especially striking. Heck, it’s striking compared to most SFF. Science fiction and fantasy writers like adventure stories, and adventures need villains; it’s a rare SFF story that doesn’t include a character it wants the reader to look down on. It’s great to end this essay on a story that just feels kind.

-

This is particularly true for the Hugos, which at any given time have a couple of writers who show up every year regardless of whether they’re doing their best work. ↩

-

This story’s Nebula nomination is as inexcusable as “The Eskimo Invasion.” It’s not even a skillfully written offensive story—it’s a long, boring monologue that eventually collapses into a lecture. What was going on at the Science Fiction Writers of America in the sixties? ↩

-

What our taboos are today is debatable but I’d suggest that modern readers don’t deal well with ambiguity, and as publishers consolidate into corporate entertainment empires they’re less and less likely to publish work that isn’t cinematic and can’t easily be sold as a Netflix series. ↩

-

Lafferty was apparently rather conservative, although this rarely comes out in his stories. ↩

-

With some searching I found an old fanzine online with the full text of the speech. ↩

-

This was a pretty amazing anthology that shaped my taste in science fiction. It had the usual 1980s problem where the editor failed to seek out stories by women, but on the plus side he did publish stories from outside typical genre SF including many translated stories. This was the book that introduced me to Borges. ↩