In the first part of this series I described Harlan Ellison’s authorial persona as a guy who’d walk up to people who hadn’t even noticed him and shout “What are you looking at?” This also describes science fiction/fantasy fans who carry gigantic chips on their shoulders about SFF’s respectability, or lack of it. One time somebody suggested they read something besides The Lord of the Rings, and it scarred them for life. In one breath they dismiss “literary fiction” as nothing more than stories written by obsolete old men about professors sleeping with their students. In the next they insist fantasy is just as good as literary fiction, dammit. Nothing can satisfy them: SFF dominates pop culture. Science fiction is taught in college courses. Octavia Butler and Philip K. Dick and Ursula K. Le Guin have been canonized by the Library of America. Still science fiction fandom lies awake worrying that, somewhere, a junior high English teacher is sneering at them.

Some years they deserve the sneers.

For instance:

1967

In 1967, three novels made both the Hugo and Nebula shortlists were Robert A. Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, Daniel Keyes’ Flowers for Algernon, and Samuel R. Delany’s Babel–17. Babel–17 is a classic novel by one of SFF’s greatest authors. Flowers for Algernon is fondly remembered even by people who aren’t into science fiction. The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is… um, a Heinlein novel.

But we’re concerned with short fiction. Here’s the list of double nominees, with executive summaries. You’ll notice it’s longer than the previous year’s. In 1967 almost the entire Nebula ballot also received Hugo nominations, the one exception being a story by Avram Davidson called “Clash of the Star-Kings.”

- Brian Aldiss, “Man in His Time”: An astronaut returns from Mars shifted three minutes into everyone else’s future.

- Gordon R. Dickson, “Call Him Lord” (Won the Nebula for Novelette): A bodyguard takes the crown prince of the galactic empire on a tour of Earth, which is maintained as an Amish-style low-tech cultural reserve.

- Robert M. Green, Jr., “Apology to Inky”: A composer goes home to visit an old girlfriend and has visions of his younger self.

- Charles L. Harness, “The Alchemist”: A chemical company discovers an alchemist on the payroll.

- Charles L. Harness, “An Ornament to His Profession”: A chemical company discovers a demonologist on the payroll.

- Hayden Howard, “The Eskimo Invasion”: You really don’t want to know.

- Richard McKenna, “The Secret Place” (Won the Nebula for Short Story): A geologist looking for a uranium mine in the desert during World War 2 meets Helen, an eccentric young woman with a connection to the land that seems to reach back to prehistory.

- Bob Shaw, “Light of Other Days”: “Slow glass” delays light that passes through it, allowing windows that show scenes from years past. A couple buying a pane discovers the seller has a secret.

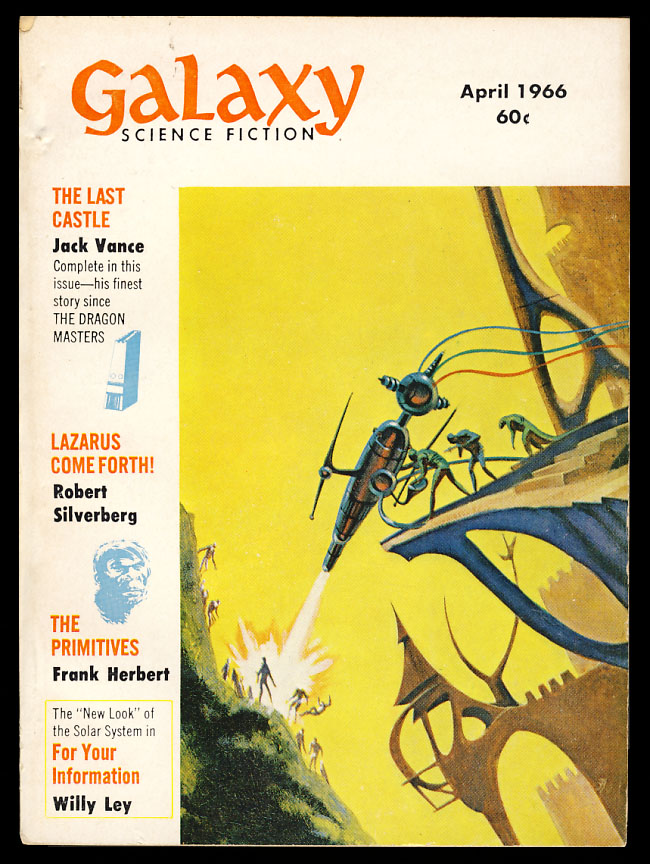

- Jack Vance, “The Last Castle” (Won the Hugo for Novelette and the Nebula for Novella.): In the far future, decadent humans who’ve enslaved four alien species face consequences.

- Roger Zelazny, “This Moment of the Storm”: A cop lives through a hundred-year flood on an alien planet and gets to shoot some looters.

The science fiction world in 1967 agreed with remarkable unanimity that these were the finest science fiction stories of 1966.

They’re mostly shit.

Okay, One I Liked

I’m being a bit unfair. “Apology to Inky,” “The Secret Place,” and “Light of Other Days” are very good and not out of place on an award shortlist, although my personal reaction to them was amiable indifference. “An Ornament to His Profession” is great and memorably weird. It opens with patent lawyer Conrad Patrick contemplating the problems waiting at work. He has a dubious contract to write. Also, an employee applied for a patent on an invention he cribbed from a student thesis he now can’t find or identify, which the company wants to co-opt or bury. Patrick recently lost his wife and daughter in a car accident and work is all that’s keeping him grounded. The scene is a genuinely good and sensitive treatment of depression and eroded self-esteem.

So he meets with the people involved in the patent and the contract. The contract guy abruptly starts explaining how he summoned the devil.

Wait, what?

If you think back you remember when Patrick was thinking of the contract he thought about selling someone’s soul. In context, it sounded like a figure of speech. But no: this chemist wants to sell his soul to get a new production process working. After all, in some sense isn’t everyone in the company selling some essential part of themselves? Patrick thinks the chemist needs to see the company psychiatrist, but he also needs to keep the guy happy because the new process is worth a lot of money. Also the chemist knows hypnosis, so, hey, maybe he can help the patent guy remember the name on that thesis. And both plots come together in this strange and ambiguous image, and questions about what it means and what Patrick really values. “An Ornament to His Profession” is uncanny and ambivalent and the best discovery I made reading these stories.

Those others, though…

Decadent Castles and Virtuous Villages

Well, last time I had praise for “The Doors of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth,” but “The Moment of the Storm” shows the limits of Roger Zelazny’s ability to punch up a banal story with great prose. It’s overlong and has little to say beyond clichés about disasters unleashing people’s worst selves. “The Alchemist” is about nothing. Like a lot of bad SF, it takes a premise and plays out the consequences but manages to avoid saying anything thematically beyond “Look at this premise!” It doesn’t even have any interesting accidental subtext. (It’s weird that two similarly-premised stories in the same series, starring the same characters, by the same writer are at opposite ends of the quality spectrum.) “Man in His Time” has interesting ideas and goes in unexpected directions but is let down by basic conceptual flaws.

I suppose I should deal with the winners. “The Secret Place” is a perfectly fine story that feels like an episode of The Twilight Zone with a happier-than-normal ending. I find I don’t have a lot to say about it in isolation.

“The Last Castle” is Jack Vance, so if nothing else it has style. Here are all Vance’s hallmarks—entertainingly amoral characters, surface-polite verbal fencing, baroque vocabulary—and he deploys them as wittily as always. But the sweet spot for Vance is a battle of wits between charming con artists. Here he’s trying to write about fatuous aristocrats realizing, or failing to realize, their civilization is built on a great crime. As good as he is at his usual business, Vance doesn’t have the specific chops he needs to develop this situation convincingly. So he stumbles into a rushed and far too neat ending. The humans repatriate the aliens and leave their castle to live in simple villages, and this is somehow all the redemption necessary. This is juvenile. “The Last Castle” doesn’t have the tools to deal honestly with its theme, and the story doesn’t bear up under its moral weight.

Vance is always at least readable, though I find if I read too much of his stuff at once it gets repetitive. Gordon R. Dickson… well, the words are spelled correctly, and he doesn’t make obvious grammatical errors, and there’s nothing to stop you from reading his stuff very fast so at least it’s over quick.

I wasn’t even born yet in 1967 and as I write I’m actually kind of angry that “Call Him Lord” won a Nebula. In 1967, a room full of professional SFF writers and alleged adults agreed “Call Him Lord” was the best SFF novella anyone had written in the last year. And it’s a bad story. And I’m not saying it’s immoral here, which is what SFF fans usually mean when they call a story bad—though I’ll be saying it in a few paragraphs, because its politics are in fact lousy. What I mean is that, judged merely on its technical merits as fiction, “Call Him Lord” is incompetent.

The hero is a plastic He-Man, simple, honest, and tough. The prince is a sneering, whining wastrel impossibly devoid of common sense and self-preservation. They’re both exactly who they appear to be the first time we see them and do not at any point reveal new depths. The hero’s briefly-glimpsed wife Just Doesn’t Understand, begging him not to go before falling into his arms crying:

Ever since the sun had first risen on men and women together, wives had clung to their husbands at times like this, begging for what could not be. And always the men had held them, as Kyle was holding her now—as if understanding could somehow be pressed from one body into the other—and saying nothing, because there was nothing that could be said.

Have they, though? Because there’s nothing convincing about this scene. (It doesn’t even make sense in context: as it turns out, Kyle’s job isn’t that dangerous.) Gordon R. Dickson writes like he’s never met a human but is trying to understand them by cobbling together pulp clichés. There is not one honest insight or accurate observation of human behavior anywhere in the story.

For science fiction “Call Him Lord” is weirdly regressive. “Call Him Lord” is about how rough, simple people are superior to decadent civilized folk. Earth sticks to 19th-century technology with just a few carefully selected modern devices. The worldbuilding is vague but you get the sense this is an agrarian society. Dickson is looking to the past for his ideals, not the future. And there’s a parallel in “The Last Castle”—Vance’s good humans reject not only slavery but also technology like radios and solar power. They live in rural villages and have a gendered division of labor, men chopping wood and women gathering berries. And the society they walked away from was already archaic, having reinvented feudalism. These stories are examples of a strand of back-to-the-land science fiction more interested in resurrecting old technologies and social structures than inventing new ones. The people who’ve adopted those old ways are often depicted as stronger, more honest and more rugged.

There’s an uncomfortable eugenic subtext here which in “Call Him Lord” becomes text. Earth is kept in technological and social stasis to maintain healthy human genetic stock in case human colonists—who are said to have wiped out at least one alien species—lose something “essential” living on other planets. Whatever that essential something is, the prince doesn’t have it. At the end of the story Kyle kills him for being a “coward.”

And I haven’t even gotten to the real turd in the punchbowl.

This Is It, Folks, the Worst Hugo and Nebula Nominee Ever

I said you don’t want to know, but I guess we’d better deal with it. In “The Eskimo Invasion” an anthropologist visits a previously unnoticed Inuit tribe who have a lot of children and say things like “Good dream protect us from bad ice. Good dream help you like us better tomorrow.” They really want to be liked. The anthropologist sleeps with a woman, because he’s a cad. (There’s a very weird paragraph where he thinks about how his “only” sexual experiences were with a long run-on sentence full of women.) In less than a month, the woman has had his baby. And this tribe worships a bear spirit who will come “when we have covered the world for him!”

“The Eskimo Invasion” may be the single most racist science fiction story ever to get a major award nomination. It is literally nothing more than fascist, white supremacist paranoia about being outbred. And the SFF community of 1967 nominated it for a Hugo and a Nebula. And the next year Hayden Howard expanded it and some sequels into a fixup novel, and they nominated it for a Nebula again.

You may have noticed the writers listed at the top of the post are all male. Apart from Samuel Delany, they’re also all white. One of the biggest factors keeping science fiction and fantasy from becoming fully adult genres—and I don’t think we’re there yet—is that their core is organized around a small, insular fandom culture. Science fiction writers, editors, and fans read the same magazines and attend the same conventions and writing workshops; writers usually start as fans. Editors rarely make an effort to look past fandom for new voices and other points of view.

This has consequences. The relevant one here is that in 1967 the genre was very hostile to women and to anyone who wasn’t white. Organized fandom grew out of clubs that were mostly white and male. Ideas like “don’t sexually harass people” were not on their radar. Meanwhile the SFF world’s insularity meant a single editor could gain an outsized influence and set much of the tone for the science fiction genre. As bad luck would have it that editor was the notoriously racist John W. Campbell. So there was hardly anyone to push back when writers and fans nominated Howard’s story.

Reading “The Last Castle” in this light I can’t help noticing the ending suggests fixing a monstrously racist society is easy. Jack Vance’s privileged humans wash themselves clean just by walking away. No further reparations are due. I’m not condemning Vance here, because amoral characters were his thing and it normally works for him. But you have to wonder what about that story might have appealed to the same people who liked “The Eskimo Invasion.”

So, Moving On

Besides racism, what other themes appealed to SFF fans in 1967?

Seeing through time. Slow glass slows the light that passes through it, showing images from years past. In “The Secret Place” Helen’s personal fairyland incorporates visions of other geologic eras. The hero of “Apology to Inky” sees himself as a small boy and a young man. Jack Westermark in “Man in His Time” exists three minutes into the future; from his perspective everyone else is three minutes slow.

What’s interesting is that this is all nostalgia—no one is looking into the future. “Apology to Inky” ends in a meeting with the hero’s older self, but otherwise everyone sees only the past. Meanwhile the people in “The Last Castle” and “Call Him Lord” have returned to older technologies and social structures. The colony in “This Moment of the Storm” resembles “the mid-nineteenth century in the American southwest.” The chemists in “The Alchemist” and “An Ornament to His Profession” revive prescientific ideas, reinventing alchemy and magic.

In 2001 Judith Berman wrote an essay called “Science Fiction Without the Future” arguing that science fiction had turned away from trying to imagine the future, instead indulging in nostalgia for the past. In 2012 Paul Kincaid made a similar argument in an essay called “The Widening Gyre”, calling science fiction “exhausted” because it had “lost confidence in the future.” It turns out this was nothing new: science fiction fans in 1967 were looking backwards.

Dead wives. If the people in these stories are nostalgic, it might be because their wives are all dead. Mr. Hagan the slow glass salesman lost his wife and son in a car accident and spends his days watching their images through his slow glass windows. Conrad Patrick, the protagonist of “An Ornament to His Profession,” also lost his wife and child in a car accident. The narrator of “This Moment of the Storm” lost a wife back on Earth and loses his fiancé at the end of the story. If you find yourself in 1967 don’t marry a science fiction man!

Alienated astronauts. Space travel is a fundamental science fiction trope, usually one fans get excited about. But “This Moment of the Storm” and “Man in His Time” are ambivalent about space travel; it’s not exciting but alienating. “This Moment” doesn’t have faster-than-light travel. Space travelers are put in suspended animation and wake up at their new planet centuries later. It’s a one-way trip into the future and once you leave your planet you’re forever out of sync with everyone else. The narrator has moved planets several times. He’s always looking for the perfect place that might exist the next solar system over, and failing to connect with where he is.

In “Man in His Time” every planet has its own local time. When Jack comes back to Earth he’s stuck in Mars time, three minutes into the future. One of the conceptual flaws I mentioned earlier is that it’s never clear how this works. Other people can bump into the place he was standing three minutes ago, and when he reads a magazine he needs help turning pages, but he seems to have no trouble eating or wearing clothes. He answers questions three minutes before anyone asks them. From his perspective, when he asks a question he has to wait three minutes for the answer.

What happens next is unexpected: Jack starts thinking of himself as a superman—everyone else is so slow. Soon he’s a megalomaniac. He plans more expeditions and thinks of himself as the first of a new breed. Meanwhile his condition baffles his wife, and his mother keeps thinking of her husband who killed himself driving too fast. (“This progress thing. Bob so crazy to get round the next bend first, and now Jack…”) Interestingly, the story ends here in unresolved mutual incomprehension. As humans move into space they’ll move into their own time-streams, getting further and further apart until they can’t understand or interact with each other at all.

But here we also come to the bigger conceptual problem. Jack’s mother says, “Jack is so strange, I wonder at nights if men and women aren’t getting more and more apart in thought and in their ways with every generation—you know, almost like separate species. My generation made a great attempt to bring the two sexes together in equality and all the rest, but it seems to have come to nothing.” A scientist studying Jack tells his wife, “You could not think what you suggest because that is not in your nature; just as it is not in your nature to consult your watch intelligently, just as you always ”˜leave aside the figures,’ as you say. No, I’m not being personal; it’s all very feminine and appealing in a way.” “Man in His Time” mixes its alienation with gratuitous gender essentialism, suggesting an unbridgeable gap between men and women. Men are egotistical but forward-looking and scientific, women are down-to-earth but imprecise. Obviously this is problematic, but the sexism is as much as anything an aesthetic problem. This theme isn’t based on accurate insight into how people work, but on received ideas about men and women. Like “The Last Castle,” “Man in His Time” lacks emotional truth. It’s possible for a story to reflect a writer’s bad ideas while still being on the whole good, but in this case the gender essentialism is lodged too deep in the story’s core and it sinks the whole thing.

Quiet Stories. The one thing I like about the 1967 shortlists is that they have room for stories about ordinary people dealing with ordinary human problems that just happen to be tied up with fantastic concepts: grief, loneliness, how people find meaning in their lives. There’s not enough of this in SFF. The genre loves superhuman characters and dangerous, high-risk problems. It often pays only desultory attention to the kind of ordinary human concerns that make stories relatable and relevant. “Light of Other Days” is a perfect example: where other SF stories take a new invention and build an absurd conspiracy or an adventure around it, Bob Shaw asked how slow glass might actually be used by real people. His answer was logical, inevitable, and devastatingly sad.

Sort of fantasy, but not really. Some of these stories, like “The Alchemist” or “The Last Castle,” have what look like fantasy premises under a science fiction veneer. Other fantastic stories, like “Apology to Inky” or “An Ornament to His Profession,” leave it ambiguous whether the fantasy elements are happening in reality or in the characters’ heads. In the sixties Lord of the Rings was only just out in paperback and fantasy barely existed as a marketing category. Writers who wanted their work to sell tended to slap a sci-fi façade over their fantasy stories.

One useful substitute for magic was “psionics.” For a modern reader “The Alchemist” has a weird tone; everybody throws the word “psi” around like it’s an unproven but familiar idea. This makes more sense when you realize John W. Campbell published the story in Analog. Campbell really believed in psychic powers; building a story around them was a good way to get his attention.

A Small World

I said earlier the SFF world in 1967 was insular. I’m not letting modern SFF off the hook, here. It’s no longer actively exclusionary—Award nominees these days are as likely to be all women as all men. The fandom that nominated “The Eskimo Invasion” is dying, though maybe not dead. But SFF is still a small world that rarely looks beyond itself. SFF writers and editors still attend all the same workshops and conventions, still mostly read each other’s stuff, and still generally come up from fandom. The main effect is that the genre is still aesthetically conservative—SFF tends to stick to a limited range of styles and subjects.

And it still has, to put it gently, variable standards. The quality of modern awards shortlists still swing wildly, mixing brilliant, worthy nominees with baffling mediocrities. Both in 1967 and today, I get the sense people nominate stories based on whether they feel good, but make no distinction between work that feels good because it’s moving or mind-expanding, and work that feels good because it flatters their preconceptions, presses their buttons, and doesn’t challenge them to grow. The fandom that nominated stories as ordinary as “The Alchemist” and “This Moment of the Storm” is alive and well.

So I love SFF, but unlike the fans I described way back at the top of the post I don’t blame people who think it’s not Literature. After all, when they look at the genre and find that, year after year, major awards have gone to stories on the level of “Call Him Lord” and “The Last Castle”—work that is flat out not up to the maturity and complexity of the stuff in the Literary Fiction aisles—what the hell else are they supposed to think?

1 thought on “The Venn Diagram of Science Fiction and Fantasy Awards: 1967”

Comments are closed.