(Spoilers from the first line this time!)

1.

Late in Up the Walls of the World, after the human protagonist Dr. Daniel Dann has transcended his mortal existence, the book throws a good-natured jab at 2001: A Space Odyssey: “I’m not going to be reborn as the embryo of humanity transcendent in the cosmos,” thinks Dann. “I’ll just be me.”

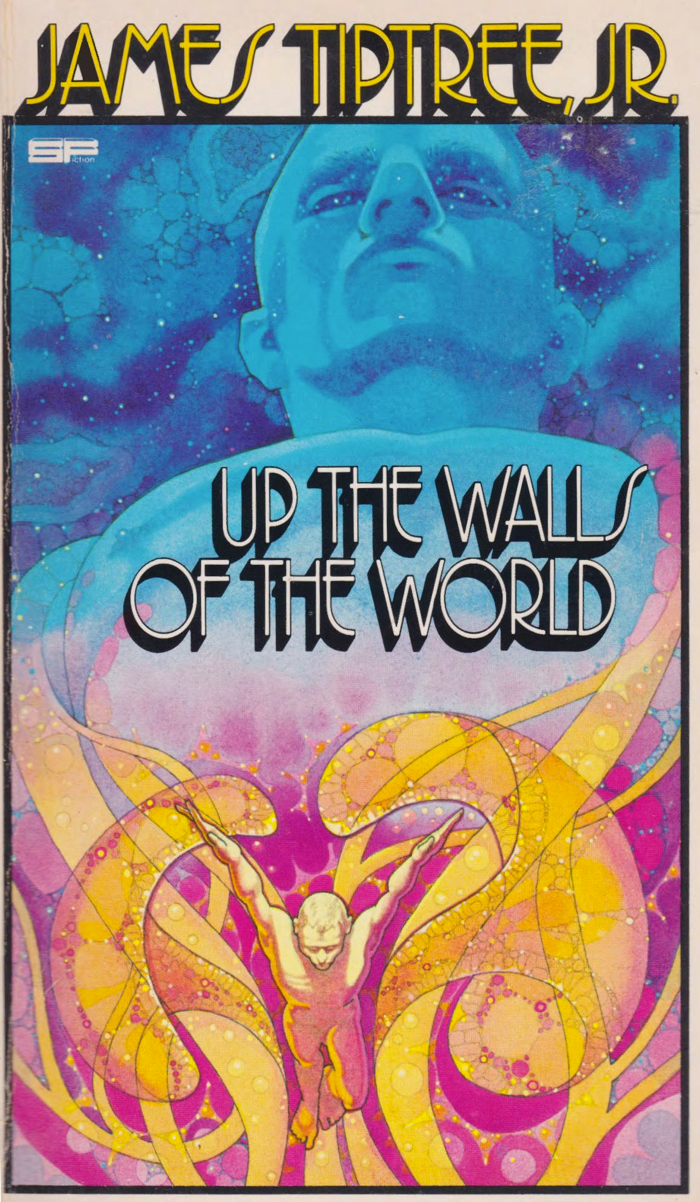

Up the Walls of the World was out of print for years. (It’s back now, as an appallingly typo-strewn ebook.) Tiptree’s novels don’t have a great reputation. They’re not as brilliantly intense as her stories; Tiptree dilutes with length. But Up the Walls of the World is still great (and better than 2001 the novel, which has its moments but mostly survives on the coattails of the superior movie).

UtWotW is structured as two alternating and converging strands with occasional interjections from a standard-issue MYSTERIOUS ALL CAPS ENTITY. Tivonel, a telepathic flying manta from the gaseous planet Tyree,[1] travels to the Wall of the World to hook up with an old lover. Her tryst is interrupted by her world’s impending destruction and certain Tyreeans’ plans to escape via interplanetary mind-swap. Meanwhile, Dr. Dann consults on a military experiment in telepathic communication while managing the drug habit that numbs his overwhelming empathy. His determination to detach from humanity is shaken when he finds himself attracted to the equally distant computer programmer Margaret Omali. (UtWotW could have stumbled here—Margaret is a generation younger than Dann, rather Spock-like in personality, and Black, and Dann initially exoticizes her a little. It would have made for an awkward romance. But where a modern SFF novel might consider romance obligatory, here their relationship settles into a more interesting friendship.) After a series of telepathic contacts and human/alien body swaps everyone ends up as telepathic presences crewing an alien machine built to preserve life from dying worlds—an apparent Destroyer that, in an anomalously eucatastrophic move for Tiptree, turns out to be a Saver.

Up the Walls of the World tells its story in a present-tense third person that sticks close to the point of view characters but allows itself moments of omniscience to let us know what they don’t. (Dann, for instance, doesn’t understand how much better his patients feel after they talk to him, even as he pulls away.)

Tivonel’s voice is all exclamation points and excited questions. She uses the word “how” primarily to marvel at things: How thrilling, how huge, how beautiful, how incredible. (Tivonel thinks less often about how to do things. She just does them.) And there’s something to marvel at everywhere, or in almost everyone. Everything is rich, strong, intense; colors are everywhere.

Dr. Dann’s internal monologue introduces itself by repeating the phrase “as usual.” He’s prone to short sentences and cursory observations, occasionally almost telegraphic. (“Specimen of young deskbound Naval intelligence executive: coarse-minded, clean-cut, a gentleman to the ignorant eye.”) Dann notices what annoys him: asinine projects, substandard door frames, disgusting electrode paste, Naval intelligence executives. The first person he pays detailed attention to is the ironically named Lt. Kirk, who Dann can’t stand. Conversely, he thinks of his patients as their code numbers (“Subject R–95”) to keep them at arm’s length, not because he doesn’t care about them but because in his experience caring hurts. (He warms to them as the book progresses, to his alarm.) Margaret’s POV enters after she leaves her body behind; her chapters are heavy on abstraction and computer metaphors. She sees herself as “ghostly circuitry.”

Tiptree being Tiptree the novel pokes at gender. The Tyreeans swap human gender roles—men carry and raise young and are more emotionally intelligent, women are more action-oriented—but still privilege male activities. Lt. Kirk is everything the Tyreean men aren’t, a symbol of self-destructive male aggression; he’s introduced after kicking a computer and almost castrating himself on the cooling fan. When he’s mind-swapped he ends up as a child—he’s the one with the most to learn from the Tyreeans. But to the extent anyone talks about Up the Walls of the World, gender is the thing they’ve talked about already. I felt more like writing about two points relating back to the quotation at the top of the post.

2.

“I’ll just be me,” thinks Dann, and he will continue to be himself for some time. Visionary or psychedelic SF stories like 2001 often end on a moment of transcendence, where the main character levels up in a cod-evolutionary sense. It’s a metaphorical epiphany, the moment after which everything is different. But we don’t learn how everything is different; the next stage of existence is indescribable. (Or the next world. Closely related are stories that transport the protagonist into the future, or an alien world, but end before we see it because it’s too wonderful to describe.)

It’s the end of the story (2001, Lafferty’s Fourth Mansions, the movies The Black Hole or Repo Man). Or the POV characters watch someone else transcend (Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Clarke’s Childhood’s End, the sublimed civilizations haunting the background of Banks’ Culture novels). Or the character de-transcends for the epilogue, returning to ordinary life happier or wiser but not much different. (This risks bathos. Either intentionally, as with the wickedly cynical punchline of Dick’s Galactic Pot-Healer, or unintentionally, as in “Threshold” from Star Trek: Voyager, unrecognized cousin to 2001: For a moment Tom Paris is omniscient, existing everywhere in the universe at once; the writers can’t imagine what comes next and in desperation turn him into a mudskipper.)

What’s the transcendent ending doing? At the simplest level, it’s a literalized metaphor. A novel is supposed to end with the protagonist changed, in a new phase of their life, ideally wiser. Ascending to a new evolutionary phase makes the change more concrete…

…But also more abstract. Growing as a person is good in itself, but in a realist novel we can also appreciate what the protagonist has learned and guess what they’re going to do next—assuming this isn’t a tragedy, where the protagonist won’t be doing anything next—because we know what life looks like. They’ll marry the guy they’d assumed was a jerk; or move back to the midwest and forget about joining the beautiful people; or go on another, hopefully less doomed, whaling voyage. Becoming a space embryo is vaguer. What does an ascended energy being do, besides hassling starship captains? What has it learned that our puny human minds can comprehend? We don’t know what transcendence means; we’re just meant to be impressed these guys transcended. At worst the transcendent SF climax is the idea of wisdom without the specifics, an escapist fantasy for SFF fans who like to congratulate themselves on how much more expanded their minds are than everyone else’s.

So the human and Tyreean cast of Up the Walls of the World ascend to a new existence as pure minds. What’s interesting is that where other stories end there, Tiptree carries on well beyond that point.

“For though he was master of the world,” says 2001, “he was not quite sure what to do next. But he would think of something.” Up the Walls of the World says: Okay. So think of something, already. So you evolved. What do you do with that?[2] What’s transcendence for? One of Tiptree’s humans loses himself in a dream world. For a while the Tyreeans live in a virtual recreation of Tyree. But what’s the point of that existence?

Margaret, having taken control of the Saver, knows its crew needs a task. Possibilities flit through Dann’s mind in a rush of em-dashes: its powers can rescue endangered species, turn back and rerun time to save lost civilizations, stop wars. Tivonel, characteristically, wants to try everything. But the important thing is to engage with the world and contribute to the general struggle against entropy instead of retreating into self-absorption. Up the Walls of the World argues growth can be an end in itself but declaring it the end is a failure of imagination. Wisdom isn’t knowing the secrets of the universe; it’s knowing what to do with them.

3.

“I’ll just be me,” thinks Dann, chagrined his cosmic transformation hasn’t granted wisdom: “But what new great necessities have I discovered, beyond the old necessity of kindness?”

On Tyree the Wall of the world is a giant stable windstorm, a mountain of air currents allowing the Tyreeans to climb high into the atmosphere. Only at the top of the Wall can Tyreean telepaths listen to other planets and, if sufficiently morally flexible, swap bodies with aliens.

The arc for these characters is about learning to go over the walls between people. Learning not to fear empathy. Dr. Dann spends the early chapters trying to be colder than he really is because he fears other people’s pain. In one of Tiptree’s more obvious metaphors, as a Tyreean Dann gains an empathic healing ability but has to feel his patients’ pain to heal them. Acknowledging others’ pain can be painful in itself, especially if we’re even indirectly implicated. And comprehending the reality of other people. Some Tyreeans are steal human bodies because to them the humans are supporting characters while they’re the protagonists. But this works the other way around: as an empathic being Dann understands “the reality of a different human world. A world in which he is a passing phenomenon, as she was in mine.” For a Tiptree story this thing is startlingly warm-hearted.

For the first time he has really grasped life’s most eerie lesson: The Other Exists. Cliché, he thinks dazedly. Cliché, like the big ones.

And, yeah, you understand why Dann isn’t that impressed by his own insights. Stated baldly, this is a cliché. Look at it one way and all Up the Walls of the World is saying is that people should be more patient with each other. Tiptree is almost apologizing here for abandoning her usual melancholy, like a goth embarrassed to be caught watching the Lawrence Welk Show. It’s like she’s asking: is this really all I’m saying?

I feel like I need to defend Up the Walls of the World from its own narrative. Stated baldly most moral insights—Dann’s “big ones”—sound like clichés. Any incompetent critic in a bad enough mood can reduce any novel to the bit at the end of the He-Man cartoon where Orko belabors the moral for the less attentive children. And some writing is satisfied with that. The equation of happiness with shallowness is itself a cliché, but it’s a cliché with some basis: the history of SFF is littered with stories written to soothe the reader with reassuring platitudes. (Although the problem isn’t only the stories telling us love conquers all, or the modern variations about how finding a properly affirming friend group solves everything—the hard SF story written to tell its readers how intelligent and tough-minded they are is the same candy, just in a different flavor.)

The real question is whether a story expects the reader to be satisfied with the platitude. And I think Up the Walls of the World passes that test. Whatever doubts the book puts in Dann’s mouth, this happy ending is hard-won; climbing those walls is difficult in ways UtWotW can only express in metaphors, not morals. As the novel ends not everyone’s problems have been solved. Again, the point of the last chapters is that transcendence means ongoing work.

Most stories circle around insights that are both profound and ordinary. Sometimes the difference between bad writing and good is simply that bad writing flattens eternal truths into cheap morals, while good writing finds complexity hidden under clichés.

-

One of the literary aliens Wayne Douglas Barlowe illustrated for his book Barlowe’s Guide to Extraterrestrials. ↩

-

To be fair, in 2001 the novel, unlike the movie, the Star Child does do something, usefully vaporizing some weapons satellites. ↩