1.

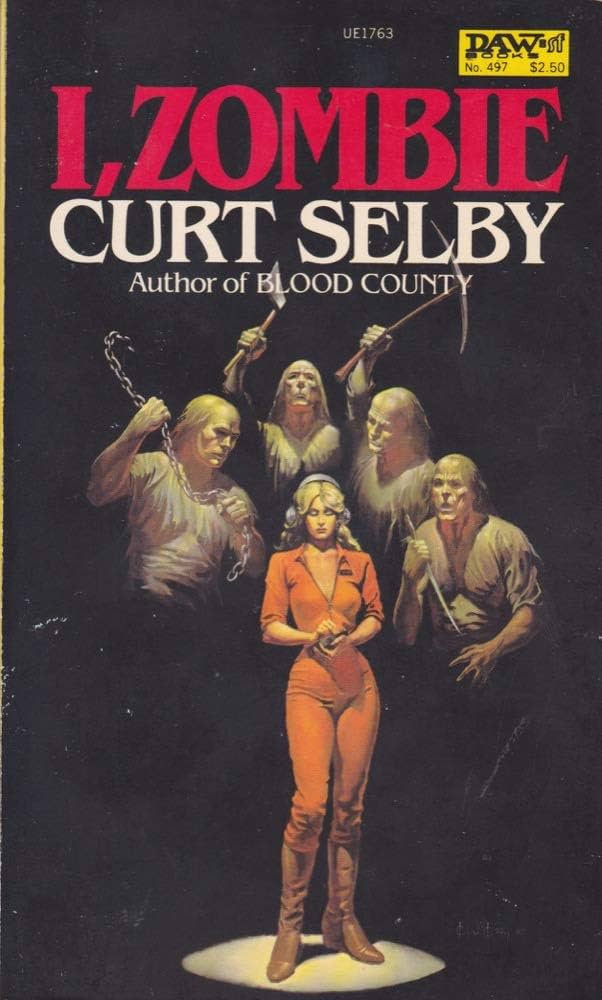

The more science fiction and fantasy you read the easier it is to guess where any given premise will go. When a book upends your predictions you feel like you’ve got something special. Doris Piserchia—like Margaret St. Clair, another neglected SF writer—has a talent for dodging the predictable narrative. Take the first Piserchia novel I read, I, Zombie (originally published under the name Curt Selby). A company uses remote-controlled indigent corpses as factory labor; the unnamed first-person narrator is mistaken for dead after nearly drowning in a frozen lake and dropped into the labor force. You can picture this story, right? It’s a near-future dystopia and a left-wing satire. The theme is the dehumanization of labor by management, and the central conflict is the protagonist’s struggle to establish their animate status.

That’s not I, Zombie.

Partly that’s because I, Zombie is a space opera set on an icy colony world called Land’s End with indigenous psychic aliens perhaps influenced by Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest. Some SFF suffers from “one weird thing” syndrome. You get one novum or fantasy gimmick but everything surrounding that novum defaults to normalcy—Occam’s SFF, careful not to multiply weirdness unnecessarily. Zombie laborers or space opera with psychic aliens. (This is often accompanied by the more serious problem that the story has only one thing going on thematically.) Piserchia is generous with her weirdness; her books have multiple weirdnesses that interact productively.

Most memorable science fiction has a touch of the outsider artist. A stylistic tic, eccentric plotting, unexpected thematic obsessions—some eccentricity flags the work as one writer’s and one writer’s alone because it would never occur to anyone else to write that way. Sometimes the touch of the outside is faint. Piserchia, though professional enough, bursts with it like Philip K. Dick.

They have no obvious common preoccupations, but Piserchia feels tonally like Dick’s close cousin. They both write matter-of-factly about a world they see from a cockeyed and paranoid side view. And both write fast and pulpy and sometimes awkwardly. In an online interview Piserchia admits “I might have done better to spend more time on first drafts but once I began a book, I wrote it at breakneck speed, finishing in 3 or 4 months and then losing interest to the point that I couldn’t push myself to rewrite.” You sometimes see her dropping explanations into the flow of her prose at the moments she realizes they’re needed instead of the moments they naturally fit. Phrasings can be awkward (“people were so busy trying to construct mental highways and tributaries that they lost sight of their premises or the need for same.”) And her first-person narrators recount even the most harrowing trials with an odd insouciance—_I, Zombie_ being a case in point. But it all works.

2.

More weirdness: the narrator isn’t trying to prove she’s alive. She’s relaxed about the whole deal, going with the flow. Before drowning she was institutionalized—she’s awkward, unfashionably tall and muscular, and was assumed to be unintelligent.[1] Being ignored by the factory staff doesn’t feel different from being ignored by doctors, nurses, and caretakers. Mix in some heavy social anxiety—“Never in my life had I been able to speak to a normal person”—and healthy contempt for people who talk about her like she isn’t there, and you get why she doesn’t speak up. It feels like the reason we don’t learn her name is she doesn’t think we ought to need it.

Instead she turns the other zombies, who she can control somewhat through her implants, into imaginary friends, reading the memories slowly decaying in their brain cells and making them talk to each other like a kid playing with action figures.

To the colonists this is invisible. They desperately, even cartoonishly, rationalize away evidence the narrator is alive. When the narrator winks at the lunch lady in the mess hall, she gasps and gapes like the villain in a Tex Avery cartoon who just ran halfway around the world and found Droopy already there. Nobody loves a memento mori: people’s eyes slide away from the walking corpses, or glaze over. One of the managers “ignored us as studiously as an alcoholic ignored hallucinations.”

The narrator does not compute. People’s minds slide frictionlessly off phenomena like a living zombie, or a sophisticated indigenous population, that threatens to complicate or upend the order of their world. Says the narrator of one colonist: “She couldn’t cope in an ordinary way… She did whatever she had to do in order not to blow her cork; she accepted the unacceptable.”

One colonist, juvenilely dubbed Peterkin, commits a murder. The investigation is half-assed; it’s another event the colonists can’t get their heads around. But the narrator has Peterkin figured out. Peterkin registers in turn that she seems more aware of the other zombies, and wants her gone. The other humans ignore and unsee things that bewilder them. Peterkin gets rid of them altogether.

You’d think he’d just whack her. Who’d notice? Instead he sets up indirect Wile E. Coyote traps—accidentally on purpose leaving her out on the ice, fiddling with the other zombies to make them attack her—which she foils by accident or by foresight. Peterkin is an ex-con with an implant preventing violent rages; its designers didn’t notice it wouldn’t stop cold, impersonal murders. On a literal level this explains why he resorts to death traps. But there’s a sense he can’t directly acknowledge the narrator is alive. An overt fight would break the rules of the game.

3.

For the narrator, undeath is play. She has free run of the colony as long as she pretends to follow orders. She happily occupies herself raiding the kitchen and sabotaging her work. At one point she destroys a domed city with an asteroid-sized glob of petroleum, an event she describes with the same distant affectlessness as the time she upends a tub of leftover salad on the guy directing the zombies on garbage duty.

One of the main arguments in David Graeber’s book The Utopia of Rules is about hierarchy and knowledge. Put simply, people at the bottom of a hierarchy understand much more about the people above them than vice versa. The people above have power over the people below, so the people below have to spend time and energy understanding who the uppers are, what they want, and how the system they all live under works; Graeber calls this interpretive labor. Conversely, the uppers have the same power over the lowers whether they understand the lowers or not.

As an assumed zombie, the narrator is so far below everyone else she’s completely illegible to the factory’s hierarchy—but, as the Fantastic Four could tell you, sometimes invisibility is a superpower. The narrator learns everything about the colonists while they learn nothing about her—and she loves it. Not that the asymmetry in interpretive labor doesn’t hurt her in some ways. And the people her fellow zombies were before they died, and the indigenous people of Land’s End. She occasionally takes a moment to snark about it. At one point one of the other zombies—who, remember, are actually the narrator having imaginary conversations—marvels at how he’s worth more to society as a corpse than he ever was alive.

But mostly she’s not thinking about this. She’s watching the colonists with mingled pity and contempt. They’re just as screwed by the information asymmetry—not that they’d ever know it. It’s the reason the narrator sees through Peterkin while the colonists find him irritating but don’t grasp that he’s a mortal danger. Their place in the pyramid of interpretive labor renders the colonists too ignorant even to keep themselves alive.

The narrator befriends the Land’s Enders, who can see perfectly well she’s alive. They don’t speak but can communicate telepathically through her implant. They think she’s different from other humans. She protests she’s just the only person who bothered to find anything out about them. The L.E.’s are aquatic; Land’s End is a water-world stuck in an artificial ice age. An atomic engine in just the right place will start a chain reaction and melt all the ice, turning Land’s End back into a planetary ocean, impossible to colonize.

So the narrator steals one. In another book this would be a major focus, a locus of complications and suspense, even the main plot. Instead, the narrator just grabs the engine from storage and walks out with it. It chugs away in the background for the rest of the book. No one is paying attention. The colonists think it’s peculiar that the ice is getting slushy but never understand what’s happening even after it dawns on them they need to evacuate. The counterintuitive way to handle a plot can be the right way: in a book about un-seeing, keeping the world-changing revolution and climate emergency in the background works thematically. And the way the colonists are slow to notice the planet warming up, even as their base progressively floods, resonates in the 21st century in ways Piserchia can’t have imagined.

4.

Like a lot of SFF from across the political spectrum I, Zombie celebrates rebellion. But the narrator does not openly, noisily protest. She’s not interested in rebellion as an identity. She looks for opportunities to take and exercise power from the place where she finds herself. Her social invisibility allows her to act as omniscient narrator and stage manager, directing the action around her while remaining unseen. She grabs the corporate pyramid from its base and inverts it, and no human ever realizes it. She’ll return to Earth with a new identity but will never be anyone’s hero.

Uniquely, I, Zombie turns social invisibility from an injustice into a wish-fulfillment fantasy for introverts, a celebration of solidarity between those who live in an industrial world but are too weird for industry. It’s a book about alienation in which alienation is pretty good, actually. I don’t think any other novel would take exactly this slant on this material. Piserchia’s point of view is unapologetically hers alone, and that’s as good an argument as any for why she still deserves to be read.

-

She says she wasn’t intelligent, and says the zombification implants smartened her up like the guy in Flowers For Algernon. But her self-esteem isn’t the greatest and it’s hard to tell how literally we’re supposed to take this; she doesn’t come off as someone who’s spent her life failing to understand things. ↩