1.

In November of 2024 Donald Trump was reelected president of the United States. The consequences were grave. American pundits, with their usual fine political instincts, zeroed in on the gravest question of all: How would families talk to each other at Thanksgiving without everybody’s mellows getting harshed? Thanksgiving used to be a meal we knew how to handle, now we’re facing utterly unmapped conversations. It’s uncomfortable, man! We just wanted pie!

An article by Lance Eliot (a “world-renowned AI scientist and consultant”) on the Forbes website had the answer: ChatGPT. What the cool kids call Artificial Intelligence, and the intelligent kids call Large Language Models.

First, Eliot suggests, let ChatGPT write a pre-Thanksgiving email for your attendees; here’s what he reports it came up with:

Hi everyone! I’m so excited to host Thanksgiving this year and have us all gathered together. This holiday is a special time to celebrate family, share good food, and reflect on all the things we’re grateful for. To make sure we have the best time possible, I’d love for us to keep the focus on what connects us — our shared stories, laughter, and love for one another. Let’s save any big debates or sensitive topics for another day. Thanksgiving is all about coming together, and I want everyone to leave feeling full (in every way!) and happy.

This is a long passage. I quote it in full to make the point that, as long as it is, it seems to say nothing. More accurately, what it says is so banal your eyes slide over it like a dead tree stump you walked past so many times you stopped noticing.

Eliot then suggests letting ChatGPT write “heartwarming remarks” to recite before everybody eats; again, his output:

As we gather this Thanksgiving, I’m reminded of the power of this table and how it brings together so many unique voices, experiences, and perspectives. It’s a chance to pause, to share not just a meal but also the spirit of gratitude and love. Today, let’s focus on the gifts we bring to each other — the stories, the laughter, and the memories we create when we’re together. Here’s to making this time about connection and the simple joy of being in each other’s company. Happy Thanksgiving!

These do not sound like the words of a human being. Not because they’re weird. They’re too normal. These are generic commonplaces, sentiments so vague anyone could express them to anyone else. What stories? Gratitude for what? Who knows. Words from nowhere, aimlessly orbiting a hole where a person should be.

Forbes also suggests you let ChatGPT normalize your family’s unique voices with dreary LLM-generated conversation starters like “If you could add one unusual dish to the Thanksgiving table, what would it be?” and “What’s one thing you’re grateful for this year?” Any family at any other Thanksgiving table could be having the same conversation—if they could stay awake through it.

That’s typical of Large Language Models. There’s a reason their output is called slop. It’s flavorless verbal porridge. What’s significant is what world-renowned AI Scientist Lance Eliot thinks you should do with this slop, and how blithely he suggests it: To avoid even the possibility of a conversation you don’t know how to navigate, let ChatGPT dictate your interactions with your family.

2.

Confession time: I hate what I just wrote. Not the sentiments; the words. Writing, for me, feels like pushing a boulder up a ski run. Every year it gets harder to pin my attention span down long enough to hook up a sentence, let alone a train of thought. (Am I getting my meaning across, or eliding points without realizing it?) My prose feels leaden. (Do I use too many words to say too little? Is there a more elegant way to say this, one I can’t find no matter how many times I revise?)

But these are the sentences I write; these themes are expressed as only I would.

3.

Apple and Google, having long ago run out of real innovations, are fixating on generative AI as the Hot New Thing. They rolled out the ads in 2024.

We’re in an office. The camera closes in on that guy—the hapless loser, the one who can’t hack it. His surfer-dude emails have everybody shaking their heads. But wait: Apple AI can rewrite his emails for him! His memo magically rewords itself into professional shape. He’s a new man! Elsewhere, a coworker has stolen a guy’s pudding and he is understandably steamed. He writes an over-the-top rant to his office mates. Before sending it he thinks better, stripping it of emotion with Apple AI—resulting in the immediate return of his snack. Another win for Large Language Models!

Through this lens we see why Forbes’ Thanksgiving celebrations ring false: they’re office-speak, the careful stylelessness of corporate communication. Frictionless, aerodynamically agreeable, calculated to confuse or alienate the fewest readers. Which, to be clear, I’m not knocking. Societies can’t function if people with nothing in common but their jobs can’t get along. Polite generalities are the social lubricant that keeps civilizational infrastructure from seizing up. But no one talks to their friends and family this way—or if you do, maybe they’re not really your friends.

What’s less obvious, because we’re so used to ads structured like this, is that they portray the worst case scenarios of human writing: these emails need cleanup. Success means never using your own words, which may express your true self but are for that reason inappropriate, ineffective, and weird. Too casual or too angry. And, hey, maybe they are. The first words that come to you aren’t always best for the situation. You could learn to vary your voice, choose your words, take different approaches as life demands. But wouldn’t it be easier to let Apple AI speak for you?

Nobody’s their true self in the office. What Google proposes is: what if we relieved you of the burden of being yourself in your leisure time? In Google’s ad a father asks the Google AI to write a fan letter for his daughter to send to her favorite athlete. The ad doesn’t show much of the results, but what we see sounds like those Thanksgiving messages: generic bromides, admiration through ad copy.

Encouragingly, the Google ad provoked widespread revulsion. Less encouragingly, Google is so deep in the AI slop mines it never occurred to anyone who worked on this ad that “widespread revulsion” might be a likely response. Who wouldn’t want a personal life as frictionless as an office memo? Who wouldn’t want CHAT-GPT in charge of Thanksgiving?

4.

It’s hard not to talk about computers without anthropomorphizing. We say a computer asks for a password or solves a math problem because granting it metaphorical agency avoids circumlocutions. So we say an LLM writes.

But the word write implies thought. LLMs don’t think, aren’t conscious, and have no point of view. CHAT-GPT’s replies come fast and haloed by a programmed aura of cheerful confidence but their speed and apparent certainty aren’t signs of knowledge; to an LLM knowing and not knowing aren’t even relevant categories. Its words are plucked from a tangle of statistics, no thought required. To massively simplify what’s going on here, an LLM’s algorithm pattern-matches words (which to the algorithm are not words, with meanings, but collections of Unicode characters represented by digits). Then it adds more word-patterns statistically associated with the existing text.

This means when you ask an LLM for a fan letter it returns a statistically likely fan letter, with characteristics shared by most writers but without the perspective or quirks of any specific person. That’s why LLM slop aspires to the condition of corporate press releases—they’re that rare genre meant to come off like they were written by no one in particular, to anyone at all.

One of the most on-point descriptions I’ve seen of what LLMs are doing is by the Crooked Timber writer Henry Farrell in his post at Programmable Mutter, “After software eats the world, what comes out the other end?”—though he undermines himself by adorning his posts with what appear to be AI illustrations. (Did they need illustrations?) I’ll take the liberty of quoting:

The more unusual a cultural feature is, the less likely it is to feature prominently in a large model’s representation of the culture. … The plausible destination that LLMs conduct towards is not entropy, or at least not entropy any time soon, but a cluster of cultural strong attractors that increase conformity, and makes it much harder to find new directions and get them to stick.

You may clench your fists and declare “I’m different! I’ll give CHAT-GPT a really detailed, personalized prompt, and get back exactly what I wanted to say.” Good luck with that. No matter how precise the prompt, LLMs give the statistical average of all likely responses, pulling as hard as possible towards bland neutrality. Words that fall into statistically common patterns will express common themes. (Stories, laughter, gratitude, and love!) Uncommon themes—thoughts specific to you, conversations meaningful to your family—need uncommon word-patterns.

Not that all your ideas are uncommon. Most arguments here have been made before and often better. (See, for example, the Farrell post.) But how I’m fitting these arguments together, the prose style, the points of emphasis, are (I hope) individual. No matter how detailed your prompt an LLM can’t understand your point of view, or speak it. AI doesn’t know what you and only you have to say. You are not statistically likely.

5.

So what is writing, anyway? You have a thought. You write a sentence, making decisions—often intuitively—about which words best fit your meaning, based not on statistics but on your actual knowledge of words. Choosing your words clarifies your thought.

Writers talk about fear of a blank page. The first step in writing is realizing your thoughts are, embarrassingly, less coherent than you knew. The blank page is a miniature moment of not knowing—one of those suddenly unmoored moments when you find yourself in a game with no playbook. You have to read the situation and think how to respond. And how do you know your response will be correct? You are not in control and for a certain kind of personality that can be ego-crushing.

Your decisions also determine your style and voice—the features that mark this writing as yours. You will stumble on words, images, and themes you’re intuitively drawn to—that, to borrow a phrase from the decluttering-industrial complex, “spark joy.” Pay attention to these; they’re pointing you somewhere, and CHAT-GPT can’t find them for you.

Then—and this is the important bit—you respond to what you wrote. Once you’ve put your thought into words you may find it isn’t the thought you, uh, thought it was—or it might spark a response you didn’t realize you’d have. Will your next sentence extend it, add detail? Clarify or modify it? Drive home the point with a stylistic flourish or a joke? Transition to something new? Or will you strike it out and start again? Writing is responding to what you’ve already written, making new decisions with each word and each sentence. Imagine you found your sentence in the wild. Say “yes, and.” You are in dialog with yourself.

Everyone who’s tried to write has had the experience of editing their first draft and stripping out clichés and overused tropes—statistically likely phrases, in other words. Sometimes a trope can stay; if they were never the right words, they wouldn’t have become clichés. But they sometimes mark points where the process failed. You reflexively shied away from the blank page, grabbed the first phrase in reach instead of thinking.

One reason LLM slop rings hollow is its bland impersonality; another is that it does not respond to itself. Words flow, ideas seem to connect. But this is an illusion: the LLM does not understand its own writing and is not reacting, just lumping statistically associated phrases together like grey goo falling out of a nozzle. If ideas connect it’s merely because commonly associated word-patterns tend to represent commonly associated ideas.

You can’t get around the problem by stepping back and asking CHAT-GPT for “editing” or “feedback.” An LLM’s feedback can only be conformist. It will seduce you away from your own themes and coax you into culling your most distinctive prose. Learning to edit yourself is, besides, an important part of writing—editing is responding to yourself, refining your thought, bringing your words and your intentions closer together.

Writing bootstraps itself; it’s why you have anything worth writing about in the first place. One sentence spurs new ideas, and more ideas responding to those—insights you had because you made yourself put them into words. You discover what you and only you have to say through the process of writing it. Take this essay—I didn’t know when I started that in the few sections following I would be drawing parallels between writing and visual art. But here they are. Why not take every opportunity to be open to surprise? What you have to say doesn’t exist until you say it.

AI doesn’t know what you and only you have to say. But it’s worse than that. If you rely on AI to choose your words, you don’t know what you and only you have to say—because you didn’t go through the process of saying it.

6.

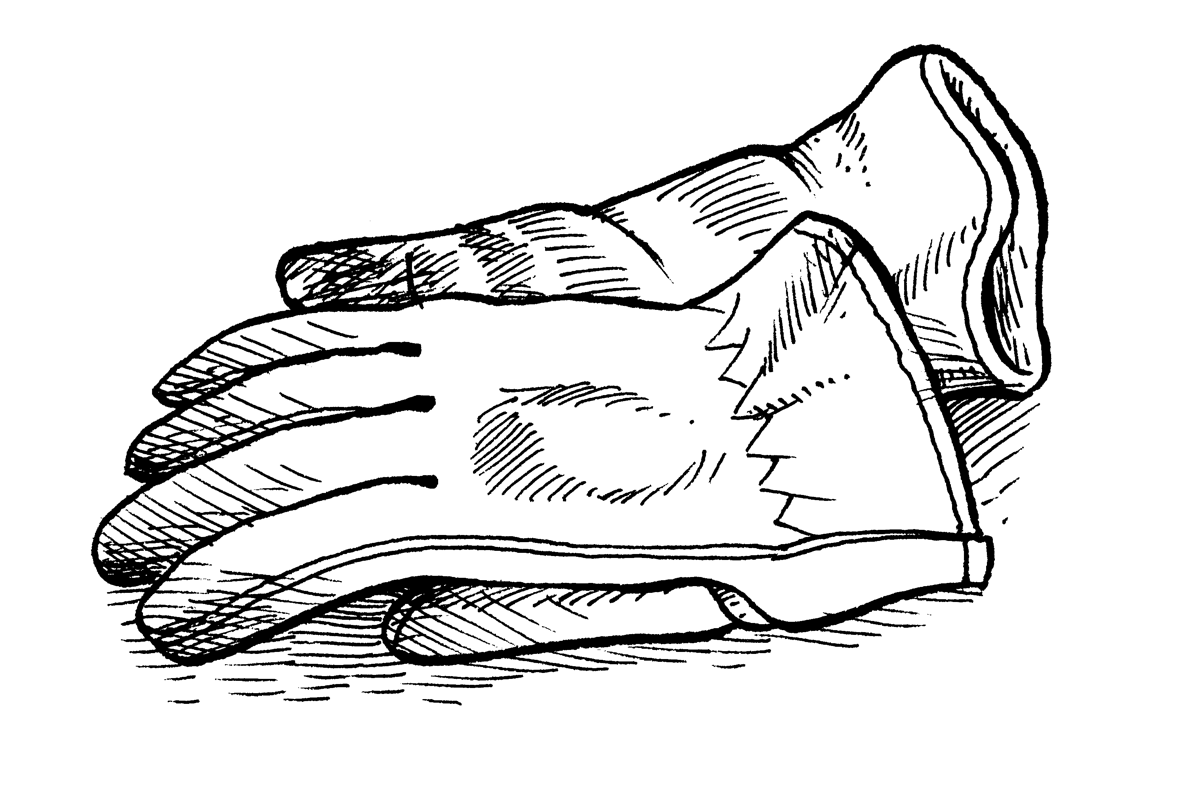

Here is a picture of a pair of gloves:

I drew this in a sketchbook some years back. It’s not, in my own estimation, all that great. If you want to disagree, thanks, but my drawings never look like the spectral impressions in my head. Despite a lifetime of practice—not enough practice, but, well, I’d still think that if I’d made myself practice more—my skills only ever developed so far. I look at the work of professional artists and wish I could draw with their skill. But these are the lines I put down. This is a pair of gloves as I draw it—as no one but I would draw it.

7.

In recent years you may have seen the internet filling with detailed yet weirdly nondescript illustrations; these are the products of DALL-E, Midjourney, and other algorithms programmed to spew images the way LLMs vomit text. Mark Chen, lead researcher on OpenAI’s DALL-E told The Atlantic “The reason we built this tool is to really democratize image generation for a bunch of people who wouldn’t necessarily classify themselves as artists.” Which is weird: image generation—or as the rest of us call it, visual art—is not a complicated skill to pick up. If you want to make movies even a beginner needs an expensive camera, actors, and assistants. All you need to draw are cheap pencils and paper from the grocery store school supplies aisle.

The idea behind DALL-E and Midjourney is that an image exists in your head, and if you feed the right prompt into a black box it will spit out that image. Having just savaged the underlying concept of Large Language Models it won’t surprise you to learn I think DALL-E is, equally, bullshit—the first problem being that the image in your head doesn’t exist. You usually have a plan, a goal, a subject in mind; but the things in your head are slippery phantasms, and the page is blank. Every drawing begins as a problem you haven’t mastered. Not a comfortable feeling; is it any wonder some would rather believe in the black box?

Visual artists make marks: pencil lines, ink lines, brushstrokes, or their virtual equivalents if you’re working digitally. You put down a mark—maybe sketch in a rough shape, maybe start with a line. You make another mark that responds to the mark you just made. With every line you are making decisions, responding to the lines you have already drawn. Every mark relates to the others in a meaningful way. Sometimes we say “meaningful” to mean “important” but I use it precisely; relations between marks, like relations between words, hold meaning. How your marks relate, how you move your tools determine your style—a part of the image that is part of you.

The image doesn’t exist until you’ve iterated through drawing a line, responding to your line, deciding what mark to make next and how to make it. I knew I was drawing a pair of gloves but I didn’t picture that precise nest of hatching until I was finished. I’ve drawn single-panel cartoons that exist because I’d drawn random images in a sketchbook and only afterward realized they belonged together. You discover your image through the act of drawing. You don’t know what it looks like until it’s done.

8.

DALL-E doesn’t know what your prompt means. It “knows” certain patterns of words are statistically likely to be associated with certain patterns of pixels, and those are likely to be associated with other pixels, and it vomits back the pixel-patterns dictated by the statistics. It’s not making decisions, it’s doing math.

The results are images that, like CHAT-GPT’s text, are statistically likely. Ask for a lion and it will give you a statistically likely lion—the laziest default lion, anyone’s lion and no one’s. A detailed prompt still evokes the most conventional possible image, an averaging-out of the infinite ways individual artist might fulfill your commission.

Forget DALL-E for a minute—imagine you’re drawing, not prompting. And maybe you like drawing eyes, or sunflowers, or cacti, or piles of rocks. Or maybe you draw people or objects in an idiosyncratic style, not quite “right” but recognizably yours. They work their way into your pictures. They symbolize something. Maybe you don’t know what it is. (You have to be comfortable not knowing.) Maybe you do but you can’t put it into words.

(Visual art, even very literal visual art, is about what can’t be put into words. You drew it because you needed to show it. Magritte painted a picture of a man with an apple in front of his face, but the important thing was how it was a picture of a man with an apple in front of his face.)

This is your symbolic language. Like your prose, it’s unique to you—the part of the image that is you. With DALL-E it’s the first thing you lose. On a basic level generative AI can’t make your marks and on a larger level it doesn’t know your symbolic language. You can prompt it for cacti but they will not be the cacti that appear to you when you close your eyes. Your art is not statistically likely.

Statistically likely art is CGI-smooth, brightly colored, with jewel-like dramatic lighting and superficially hyper-detailed textures that on closer examination doesn’t resolve into anything coherent. It’s the style you’d get if a stoner hired Thomas Kincade to airbrush his van. At least, that’s the statistical average of the styles in these algorithms’ training data—called a corpus, appropriately, since the results look dead—which seem heavily weighted towards the kind of art that appeals to the kind of men who are offended when a video game character is a woman. Also a lot of CGI-heavy Hollywood movies, evidently, since prompting for a movie still, even sans description, often gets you an actual movie still.

But can’t you prompt DALL-E for another style? Sure. Ask for an impressionist painting, or an editorial cartoon, or graffiti—or, if you’re shameless enough, the sad zombie caricature of a specific artist whose work got trapped in the training data. It won’t be your style, or even your own spin on an existing style. It will be an averaging-out of everyone else’s styles.

Oh, you’re training the algorithm on your own work? Sorry, that’s still not your style, just a dead approximation. First, style is a living thing; it develops and grows. The algorithm is stuck with your input. That’s why I say “dead”—it’s static. Second, the algorithm mixes your style with the rest of its corpus, and the statistical nature of the software naturally pulls away from reproducing anything of yours that is too individual or idiosyncratic—and those are the important parts.

Fans of generative AI insist it’s only going to get better, more sophisticated, more creative, more able to come up with the correct number of fingers. Maybe, although there are equally good arguments that AI is close to hitting a wall. But it doesn’t matter how good it gets at what it does, because what it does has no purpose. AI cannot be you. Without consciousness, a point of view, AI can’t even be itself.

All AI art has one thing in common: no matter your taste, no matter the style they simulate or how many fingers they get wrong, they will never confound you. You will never stand before a piece of AI art and not know how you’re meant to respond. (How you do respond is up to you. But you’ll know how you were meant to.)

The fundamental quality of good art is surprise. You look at art and have a moment of not knowing and that’s how it gets you—opens your mind to puzzlement, shock, or delight. Makes you think, or startles you with a glimpse into another human mind not at all like yours. (Or, maybe, unexpectedly like yours.) Generative AI pulls its output towards the statistical center, the common and the conventional. Its images are… let’s say expectable. Comfortable images that won’t alienate, disconcert, or puzzle the people whose tastes influenced the AI’s corpora. Visual muzak.

9.

Prompting is not a new skill; any magazine editor knows the drill. Give us a thousand words on waffle irons. Give us a black-and-white single column spot illustration to go with it; use this waffle iron from our advertiser as a model.

When an editor commissions an article, does the editor get the credit, or the writer? Whose thoughts does it convey?

When an art director asks for an image, did the art director draw the picture, or the artist? Whose style is it drawn in, whose marks are those? Whose symbolic language do you see?

10.

Okay, so here’s where I’ve been heading all along.

The historian Timothy Snyder published a book called On Tyranny during the first Trump administration. More recently he’s published On Freedom, examining his philosophy of freedom. One of the more unexpected virtues of freedom Snyder identifies is unpredictability.

To oversimplify Snyder’s ideas, free citizens are unpredictable. You don’t know how they’ll respond to a situation because their decisions arise from individual, idiosyncratic experiences, values, and points of view. Not that predictability isn’t good to some extent. It doesn’t help anybody when we can’t predict whether a driver will stop at a red light. But repressive societies want standardized citizens—interchangeable parts who respond predictably all the time.

When election day comes around, when you face a moral dilemma at work, when you’re dating, when you make small talk at a party—authoritarians want every Jonbar Hinge swinging in the least surprising direction. Preferably the direction that benefits authority, but if you’re predictable in any way, even a rebellious way, any half-skilled authoritarian can plan around you. Okay, you’re their enemy; the point is they don’t have to think about your being their enemy. Authoritarians’ worst moments are the moments of not knowing—the liminal blank-page moments when they’re not the masters of the situation.

Which brings us to art and writing. In a free culture they wander all over the damn place, from a conventional yet recognizably individualist middle to a Babel of weird and baffling avant-gardes. An authoritarian culture has a narrow range of acceptable styles and messages. Conformity might be enforced through official censorship, as the Soviet Union enforced socialist realism. Or peer pressure and private power might enforce conformity, as in Hollywood in the days of the Hays Code.

Or you might voluntarily make yourself predictable by outsourcing your speech to an algorithm guaranteed to express nothing new, surprising, disquieting, or unique—only conformist remixes of commonplace ideas, forever.

11.

AI advocacy is especially pernicious when it’s presented as “democratizing” expression for the disadvantaged or disabled. Generative AI doesn’t empower its users, it filters them. If its users have ideas outside the mainstream putting their writing through CHAT-GPT makes those ideas less audible. If those users are outside the mainstream, their ideas probably are as well. Those might be the ideas the rest of us need to hear.

But you might not be listening. Once you’ve stopped speaking unpredictably the next step is to stop hearing anything unpredictable. In another Apple ad a man asks Apple AI for quick one-sentence summaries of papers he hasn’t read. Judging from the results when Apple AI tries to summarize news headlines—it’s claimed a murder suspect shot himself when he’d simply been arrested, and insisted Trump’s tariffs were affecting inflation before his inauguration—this might not go well for him. But setting aside the inaccuracies, what do AI summaries leave out? Anything too improbable to make it through the algorithm. The marginal. The unexpected. The new.

You can get used to not hearing anything new. How can you miss what you by definition weren’t expecting?

“This isn’t an avant-garde literary salon,” you protest. “I’m using AI for routine office tasks.” Well, sure. But a year later you’re sending your co-worker LLM memos about a problem, and they’re sending LLM memos back, and you’re both reading LLM summaries instead of the memos, and nobody has even an inkling of a new idea that would make your jobs less exhausting.

A generation of students are feeding their homework into LLMs and getting answers that work well enough, sometimes. Again, they’re avoiding the moment of not knowing—the humiliating acknowledgement of a situation they have not mastered. CHAT-GPT chases the anxiety away in seconds. But all they learn is how to dodge developing problem solving skills. How many problems will future generations fail to solve because they outsourced their imaginations to algorithms that can’t have new ideas?

You don’t know what you think until you’ve gone through the process of thinking it. You can’t know something until you admit you don’t know it. You can’t have new ideas without working through the blank page.

Some people ask LLMs for relationship advice—less embarrassing to be vulnerable with a chatbot than with your partner. Others start relationships with the chatbots themselves, lovers who will never challenge them. Companies promise to bring your dead loved ones back to life, or at least versions of your dead loved ones statistically averaged with everyone else in their LLMs’ corpora. Until the public, hearteningly, recoiled in disgust, Meta toyed with plans to add LLM-based “users” to Facebook to interact with users like fellow humans.

In the 1960s Joseph Weizenbaum developed a chatbot called ELIZA. It was simple, just rephrasing the users’ statements back at them, but some users had trouble distinguishing it from a person. CHAT-GPT is more responsive and programmed with the blandly chummy sycophancy of a car salesman; people want to believe in it. You stop noticing the difference between people filtered through AI and people in the raw. You stop noticing the difference between people and AI altogether.

The Peterskapelle church in Lucerne, Switzerland, as an “experiment,” installed an LLM Jesus to chat with tourists and parishioners. Irreligious as I am, I was surprised how I recoiled from the idea. The real Jesus was a political radical who championed ideas far outside the mainstream. What can a Jesus who algorithmically defaults to bromides and commonplaces teach?

12.

American conservatism is a collection of unjustifiable moral panics. Conservatives hate it when schools teach their children lessons they never learned, when the kids start a subculture they don’t get, when the library lends books that aren’t about them, when they hear other languages spoken in public, and when strangers show up in their neighborhood. They’re longstanding homophobes and cruel persecutors of trans and nonbinary people.

There are a lot of impulses behind all this—one big one is a craving for hierarchy, with white cis men on top—but for our purposes the most relevant impulse is… well, not precisely fear of the unknown. It’s fear of not knowing. The idea you were never exposed to, the person you can’t instantly classify. The humiliating unmoored moment when you find yourself in waters you don’t know how to swim. The conservative mind—politically Conservative and small-c conservative alike—never wants to have to think for a single second about how to respond to anything or anyone. For that it needs a world where everyone makes the same decisions… or rejects the not-knowing that is the fundamental precondition of an imagination.

Every culture has a center. In conformist cultures it’s a black hole. Free cultures exercise less gravity. Generative AI’s gravity pulls inexorably towards the predictable and generic, and away from, well, you. When you use generative AI you are predictable, and you cannot be both predictable and free.

And the hell of it is that no one is doing this to us. There’s no conspiracy, no shadowy cabal deliberately withering our minds in a bid for power. Yeah, it’s possible a few executives in the tech industries have thought this through. But mostly we are doing this to ourselves. Most of the tech execs hyping AI have no ambition beyond turning new technologies (of which there are fewer and fewer to pick from) into money. The rest of the AI boosters are middling marketing gurus, allegedly world-renowned consultants, uncritical tech fans who get dopamine hits from generating inane pictures, and students taking shortcuts on homework. What they all have in common is the fear of not knowing. Generative AI lets them skip over their blank pages and in return it is training them, in every aspect of their lives, to settle for slop.

Generative AI tells us to fear the blank page, the person who is not socially legible, the problem with no readymade prescribed solution to hand. To run from the unmoored moments when we don’t yet know what to think. Here, take these predigested ideas to save you the inconvenience of thinking. Filter the world through your LLM until anything strange looks unthreateningly familiar. That’s the thing about the cultural center: it’s predictable, but it’s a comfortable kind of predictable. It’s the old tree stump you’ve walked past a hundred times, and old tree stumps rarely deliver jump-scares. Set your mind on automatic pilot. AI asks nothing of you, and you will never need to learn anything new.

Generative AI is an elixir for the elimination of not-knowing. That this also serves totalitarians and fascists is merely a side effect.

I’m haunted by the specter of families greeting each other with slight variations on the same Thanksgiving toasts. Galleries full of art that all looks vaguely the same. Novels nobody really wrote and nobody really reads. A landscape in shades of greige. This might appeal to a conservative mind. Heaven, as the song goes, is a place where nothing ever happens, and they believe that unironically. For the rest of us—well, it’s hard to forget the place where nothing ever happens is a place you only get to after you’re dead.