1.

There’s a style of nonfiction I cannot stand. It’s written by journalists straying into scholarly subjects—history, sociology, science. They write about these subjects by writing about themselves. Their “research” consists of traveling and interviewing experts. They spend half the book narrating the interviews, and giving physical descriptions and miniature biographies of the interviewees, and telling us about the places they travelled to and what they did there. Often the only insight offered by any of this is that a historical site related to the subject of the book still exists as a tourist destination (be sure to visit the gift shop). These books read less like serious attempts to explain their subjects than like high school “what I did on my summer vacation” essays. It’s a lousy format for nonfiction. But it works great for fictional nonfiction.

Giorgio De Maria’s The Twenty Days of Turin was written in 1975 and is set sometime around the end of the 20th century. Ten years earlier, in Turin, an obscure series of events began with a mysterious Library and ended with insomniacs beaten to death in the streets. The nameless narrator is writing a book on the subject. He talks to the sister of the first victim, and a lawyer who recalls hearing inhuman cries in the night, and a scholar whose radio apparatus recorded voices arguing over the airwaves. It all leads up to a big reveal (which I’ll spoil in part two) that, described baldly, sounds like the premise for a Monty Python sketch. But in De Maria’s hands it’s unsettling.

The Library is housed in an old hospital, and run by clean cut young men in suits, and doesn’t house ordinary books. It accepts manuscripts from its members—memoirs, essays, personal ads, diaries, rants, whatever you’re compelled to pour out of your brain onto the page. You can read anyone else’s writing, and if you feel a connection the nice young men will, for a fee, give you the author’s name. It’s all about getting people to open up to each other. “The prospect of ‘being read’” is what the Library offers, and the writers’ outpourings are compulsively confessional.

Every review of The Twenty Days of Turin mentions how much this sounds like social media. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, the handful of corporate sites that took the place of personal websites as our homes on the internet. People put their lives on display to strangers to for the promise of a connection. But the Library’s writers and readers rarely meet. Getting names is just a way of going deeper into voyeurism. Writers get paranoid; any stranger might know their secrets. The Library “helped to furnish the illusion of a relationship with the outside world: a dismal cop-out nourished and centralized by a scornful power bent only on keeping people in their state of continuous isolation.” Having written, the Library’s patrons become insomniacs and spend their nights wandering the streets.

Facebook and Twitter encourage a constant churn of content, an anxious compulsion to keep performing for the algorithm, propping up the metrics that embody our virtual selves, lest our follower count dwindle: “Do you think human beings are really like bottomless wells? That we can drain ourselves endlessly without sooner or later finding our souls depleted?” People who’ve written for the Library feel dried out, drained. De Maria consistently uses water metaphors here: one man “felt that the bottom of his lake had suddenly been raised, as if someone, from below, had pushed it up… And that there was no real difference between the depth of the lake and anything else, not the city, not the asphalt, not this house…”

Social media feeds spray the whole world through a single firehose: news about climate change and the reaction to the latest Marvel movie and the most recent Supreme Court case and your friend’s cat photos all mix together and all get the same emphasis. Everything feels as important as everything else. The audience stares back through the same hose, leading to context collapse: different audiences cross into each others’ worlds, see each others’ conversations, and wildly misinterpret them. One person’s tossed off comment about a movie becomes someone else’s unforgivable aesthetic crime.

Sometime after the insomnia begins the lawyer hears the eerie howling, and the radio technician records strange conversations preceded by a sound “as if hundreds of mouths were dipping into a monstrous water hole determined to tap it dry, as if a thousand-year-old thirst had finally found a wellspring where it could drink its fill.”

But whose thirst?

2.

So, that premise. Turin’s monuments, its statues (“Those who are unmoving, those who are beyond suspicion—as far as they are inert and familiar—and yet soaked in blood from head to toe”), are slurping up all that soul-energy and coming to life to battle each other, grabbing insomniacs by the ankles and swinging them like Punch-and-Judy clubs to batter each other. Which sounds ridiculous. But it doesn’t feel ridiculous when you read the book. Partly that’s because De Maria’s great grasp of horror technique. He makes great use of ambiguity: is that mysterious pale nun also the statue from a few pages ago? What are those heavy footsteps behind the apartment door? But even the basic premise is not inevitably silly. I mean, imagine one night a howling Lincoln Memorial stomped into your neighborhood, grabbed you up, and smashed you over one of those Confederate monuments. It’s downright disturbing, and not just because you’d rather be smashed over a less crappy opponent. The image takes on a certain seriousness because it’s a potent metaphor.

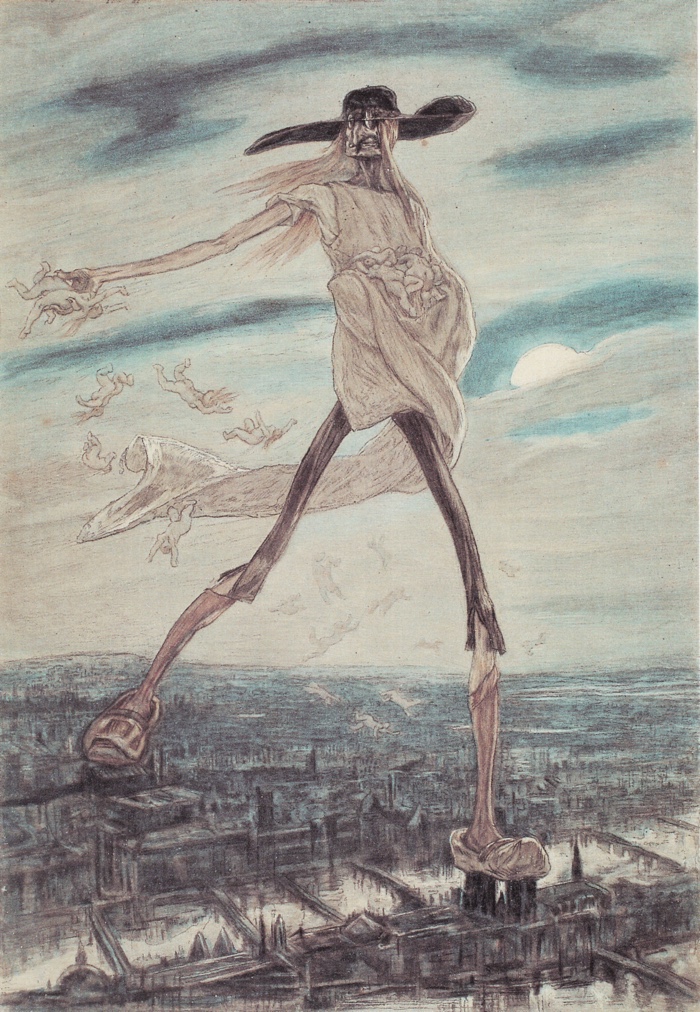

(The covers of both the original edition and the English translation feature “Satan Sowing Tares,” a print by the Symbolist artist Félicien Rops. A gawky, emaciated giant strides through a city scattering human bodies over the streets. It’s both funny and not.)

De Maria wrote The Twenty Days of Turin during the Years of Lead. This was a period of terrorist violence—bombings, assassinations—that lasted from the late 1960s through the 1970s, perpetrated by both left-wing militants and neo-fascists. (Some of the latter may have had help from members of Italy’s Secret Service.) The narrator gets on a plane to get away from the statues. In an ending that recalls the airline hijackings common in the 1970s, it doesn’t work out. You can see how The Twenty Days of Turin captures the feeling that, any day, your life could randomly end in the explosive expression of a stranger’s fascism. (The Years of Lead were perpetrated by left as well as right, but the threat here feels specifically fascist: the monuments, representing purportedly great men from Italian history, recall fascism’s hero-worship and obsession with a mythic past.)

But the metaphor takes on alternate meanings looked at through the lens of social media. Recently on Twitter the editor of a small poetry magazine made the anodyne observation that not many people read contemporary poetry and it’s not politically powerful. Her magazine fired her the next day, because the poets of Twitter lost their collective mind. Poem Twitter reacted to the suggestion that maybe a poem read by twelve other people, also poets, wasn’t going to change the world with all the composure of Dracula when Peter Cushing waves a cross in his face. (“Let me guess—you don’t recycle either,” tweeted one person who was somehow not a fictional character in an Onion story.)

If you’ve spent any time at all on Twitter you’ll have noticed overreactions are a near-daily occurrence. Twitter makes people mad. Facebook makes people mad. Nextdoor makes people mad and also racist. That’s by design. Social media algorithms lean into pissing people off because anger is engaging. Engaging users, for the benefit of advertisers, is how social media companies make money. Outrage is profit. The more sour and combative we get, the more Mark Zuckerberg’s stock options are worth.

And it’s over the most trivial garbage you can imagine—major pile-ons are never over anything that matters. Nobody’s compiling receipts on right-wing politicians who vote for abortion bans or to end eviction moratoriums. Social media gets angry about directors who don’t like superhero movies, ambiguous short stories by unknown authors, and the dubious pontifications by people with no real power or influence. Outrage is profit, but it’s got to be outrage that doesn’t upset the status quo.

Why do these companies build these websites? Why is everyone else, from corporations to political groups, so anxious to spend their advertising dollars targeting such miserable people? What is this depressing Rube Goldberg machine for? Well, mostly to help people who already have more money than they’ll ever need collect even bigger piles of money. To us, the users, the goals of the People In Charge matter about as much as Martin Scorsese’s opinion of Ant Man.

What are De Maria’s monuments fighting over? Not a lot. They’re jealous of the views from each other’s pedestals—something that matters not at all to the people they’re killing. Turin’s insomniacs are weapons in someone else’s fight. Most wars are, down at their roots, cases of powerful people bashing much less powerful people against each other for causes that don’t make much difference in those people’s lives. If The Twenty Days of Turin reminds people of social media, maybe it’s because, in a less deadly sense, that’s also true of the people who spend most of their time on Facebook and Twitter getting angry.