History

The Boston Molasses Flood of January 15th, 1919 was always one of those events trotted out wherever weird and strange historical events were compiled. In the days before the internet details were sketchy; usually you’d encounter a brief summary in a magazine article or a trivia book. You might have thought of it as a harmless, quirky Wes-Anderson-movie kind of disaster, had Wes Anderson been a thing at the time. You know: molasses flowing down the street past a sad but knowing Bill Murray while an old Rolling Stones song plays.

Actually, the molasses flood was not a joke. It was a blast of 2.3 million gallons of molasses moving in a 15 to 25 foot wave at 35 miles an hour.[1] Pictures taken at the time show buildings smashed to pieces. Twenty-one people died, mostly from suffocation. Horses caught in the muck had to be shot. The cleanup was awful: people tracked the molasses all over and eventually the whole town was sticky. Even the molasses itself was serious: the United States Industrial Alcohol Company used it to distill alcohol for munitions.

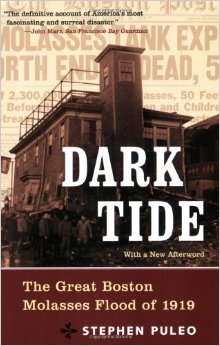

Details on the molasses flood are more available now, partly because they’ve been pulled together on the internet. You can find even more information in the single book about the flood, Dark Tide by Stephen Puleo. What’s great about Puleo’s book is that it doesn’t just describe the flood: it explains how the flood was not just weird, but actually important.

The molasses flood wasn’t a freak accident. The U.S. Industrial Alcohol Company’s tank was junk. The Industrial Alcohol employee in charge of construction, Arthur Jell, wasn’t an engineer. He approved a tank that wasn’t sturdy enough to hold two million gallons of molasses and didn’t bother with basic safety checks like testing for leaks. People who lived and worked near the tank told U.S. Industrial Alcohol they could see molasses leaking from the seams and running down the sides. The company responded by painting the tank brown.

Asked why their tank had burst, the Industrial Alcohol Company had a ready answer: anarchists. This was not as stupid as it sounds. Anarchists were the big terrorist threat at the time, and, remember, the company used the molasses to make alcohol for munitions, most recently for use in the First World War. This was war molasses, and the company really had received threats to blow up the tank.

But the tank wasn’t just shoddy, it was obviously, embarrasingly shoddy, as the subsequent investigation had no trouble establishing. Despite agreeing the tank wasn’t up to code, the grand jury didn’t indict any Industrial Alcohol Company executives for manslaughter. (From a 21st century perspective, maybe it’s amazing they considered indicting corporate executives at all.) But there was one important consequence. The government of Boston decided that before their building department would issue a construction permit more detailed architectural plans would have to be filed with the city, including all engineering calculations, certified by an actual engineer. Cities all over the U.S. followed Boston’s lead, tightening their building codes and increasing their oversight of construction projects and engineering requirements. If the buildings in which you live and work haven’t fallen down on you lately, you can thank molasses.

Drama

Dark Tide is a good, well-researched book. I’m going to get into some caveats here, and they’re big caveats, but I really do recommend it. It includes details on the flood you won’t find anywhere else. Sometimes, though, there are reasons you won’t find those details anywere else. Like, at one point Puleo describes Arthur Jell in his office getting some concerning news about the tank, and we get this line:

“‘The tank will be safe,’ Jell said aloud, sitting alone in his office.”

He was alone when he said this? Then… how do we know? Did Jell have one of those invisible offscreen butlers, like in Citizen Kane?

That would be cool. But, no, apparently Puleo just made it up:

In some cases, I have built the dramatic narrative and drawn conclusions based on a combination of primary and secondary sources, and my knowledge of a character’s background and beliefs. For example, Hugh Ogden’s[2] letter to Lippincott from the Cosmos Club in Washington, D.C., is real; Ogden’s concerns about the manner in which the country has been thrown into turmoil is my interpretation based upon what I know of Ogden’s patriotism and his soldier’s attention to order.

Dark Tide tells us things about people’s thoughts and feelings the author could not possibly know. It doesn’t sound speculative–it states them confidently, as facts, with the same omniscient tone novelists use with their characters. This is truthiness presented as history.

That novelistic tone is the key to what’s wrong here: Puleo’s desire to build a “dramatic narrative.” The line I quoted comes just before a section break. It’s narrative punctuation, a cliffhanger–a strong image to imprint itself in the reader’s memory as the subject changes. (And note it’s not just a strong line but a visual image, like you’d get before a scene change in a movie–a character is in a setting, saying something aloud. This is history written in Novelization Style.)

This is not a quirk of Dark Tide alone. Many popular histories lean hard on narrative. As much as possible the authors want their books to read like novels. (And maybe like movies–nonfiction books get optioned for film too.) Which misses the point of nonfiction. A lot of topics work better when not artificially squeezed into the shape of plot, suspense, and characterization. For all that history superficially resembles story, it’s usually one of those topics. I mean, it’s not like Dark Tide’s central arguments are weak–how the molasses flood came to happen, and how it influenced engineering standards, are dramatic enough without being dramatized.

But that’s quibbling. The real problem is how the dramatized scenes distort the history–the confidence with which Dark Tide narrates scenes that were never recorded in any form, and claims to know the hearts and minds of people long dead.

Switching gears for a moment… I’m reminded of something the novelist Guy Gavriel Kay has said more than once, most recently in an article at Boing Boing. One reason Kay writes fantasy instead of historical novels is that, even in a novel, he’s not comfortable imposing (his word) his own invented personalities and opinions on people who really existed. It’s arguable whether this is actually a problem in fiction; even Kay acknowledges good novels have been written about real people. But I’d argue that historians have a responsibility to tell the truth, as far as they know it, about real people.

Sometimes we do know with reasonable certaintly what a person was thinking or doing in private–sometimes they left diaries or letters or court testimony that tell us. (At least, they tell us what they’d have liked us to think they were thinking!) But usually we don’t know, especially when we’re talking about passing thoughts as opposed to fundamental beliefs and motivations. Historians may know the reasoning behind most of Lincoln’s decisions during the Civil War, but can’t claim to know what passed through his mind during breakfast. There’s nothing wrong with speculation–discussing what the author thinks a person was probably thinking, or probably doing–but it should be written as speculation, not omniscient narration, and supported by facts. Nonfiction takes humility, a willingness to acknowledge sometimes the author just doesn’t know. Otherwise writers run the risk of coming out with passages like this one, about the Industrial Alcohol Company’s lawyer:

But in the places none of us like to visit—the darkest corners of the mind, the coldest reaches of the heart—Charles F. Choate must have felt a sense of perverse satisfaction when he received word on the afternoon of September 16 that someone, most likely an anarchist, had detonated a deadly bomb on Wall Street in New York City.

Or this one about John Urquhart, a boilermaker who worked on the tank:

Urquhart knew that all of these issues were out of his control and would be decided by smarter men.

I mean, maybe Urquhart did think the people who made the Big Decisions were smarter than he was. Maybe he mentioned it in a diary somewhere, or in testimony during the lawsuit, or something. Without checking Puleo’s sources, I have no clue. Dark Tide has a problem common in popular narrative history: the novelistic style is meant to be exciting, but reading it feels like harder work than reading an academic tome by a professional historian. Reading this style of nonfiction is a tiresome exercise in sorting source from speculation, the literary equivalent of picking the fish bones out of ten pounds of chopped tuna.

In recent posts I’ve complained fiction that uses the style and narrative techniques of nonfiction was underrated; now I’m complaining nonfiction techniques are also underrated in actual nonfiction. I like fiction in the style of essays or histories, but I guess it doesn’t work the other way around!